|

By Susan Biddle (Different Perspectives volunteer)

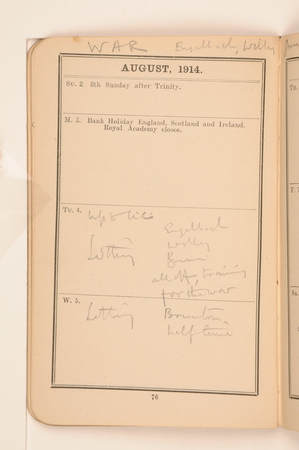

We all know about the trenches dug in Flanders … but trenches were also dug in Egypt during 1915 for a rather different purpose. In 1915 the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF, now the Egypt Exploration Society - EES) was granted a special concession to procure objects for a small group of American Museums who provided funding in exchange for a share in any finds. A team, led by an American, Professor Thomas Whittemore, and Gerald Wainwright, one of Petrie’s pups, excavated at Balabish on the East bank of the Nile in Middle Egypt, about 20 miles from Abydos. Although the United States did not enter the war until 1917, Thomas Whittemore divided his time during the war years between Egyptology and war work, first for the British Red Cross on ambulance duty in France, and subsequently with refugees in Russia. Wainwright had been interested in Egypt from a schoolboy when his mother told him about a slide lecture given by Amelia Edwards, one of the founders of the EEF. At evening classes in Egyptian and Coptic at University College, Bristol, Wainwright met Ernest Mackay, one of Petrie’s assistants. Wainwright was so thrilled by Mackay’s descriptions of fieldwork with Petrie that when he finally met Petrie at a lecture in 1907, he asked to join his dig team. Petrie told him there were no posts available but he could come as a volunteer, so aged 28 Wainwright took a cargo boat to Egypt, equipped with just £25. He worked with Petrie until 1912, after which he worked in the Sudan, Abydos and Sawama, as well as with Leonard Woolley and TE Lawrence at Carchemish. When war broke out, he volunteered but twice failed his medical so was available to lead the EEF team. As usual, most of the excavation was done by local men and children, many of whom would have had considerable archaeological experience. The team led by Whittemore and Wainwright excavated at Balabish between March and May 1915, discovering two distinct cemeteries: one of Pan-grave people (so called by Petrie because of the shape of their burials) and a later one from the New Kingdom. The Pan-grave people were contemporaries of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period (broadly 2000 – 1500 BC), and were famed as archers and nomadic cattle breeders. My first job as a volunteer at the EES was to scan the Balabish tomb cards and negatives so these could be made available on the EES website so it was great to be able to use this resource in my later research for the Petrie Museum’s World War I project. The pan-grave burials included horns and horn objects, reflecting the importance to them of cattle, and archer’s equipment. For example, burial 201 included a body covered in leather and buried with a horn knife and bracelet, an archer’s leather wrist guard and a bundle of yellow sinews which Wainwright suggested were bow strings as they seemed too thick to have been used as thread. Many of the Pan-grave and New Kingdom burials included sandals, giving an opportunity to compare footwear fashion: Pan-grave sandals were one thickness of leather, with square or rounded toes, and might have a few beads stitched into the leather (on right); New Kingdom sandals were several thicknesses of leather, had pointed toes, and might be dyed red (on left). In both periods the straps seem to have ended in a large knot under the toes, which must have made walking excruciating. This may not have mattered, if sandals were ceremonial items to be carried as a status symbol (as on the Narmer palette), rather than being worn. Wainwright gave a preliminary report on the work at Balabish in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology (JEA) in 1915 (with the final report delayed by the war until 1920) and also gave a public lecture at the Royal Society in Burlington House in Piccadilly, London. The JEA reported that despite wartime constraints, his lecture was well-attended and the EES Committee had “every intention of proceeding with our programme of lectures as usual during the winter”. Other fieldwork also continued. The absence of officials and general demoralisation caused by the war led to a revival of tomb-robbing. In 1916 Howard Carter was asked to intervene in trouble between two rival bands of robbers skirmishing over a recently discovered tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Carter arrived at the scene at midnight, to find the end of the robbers’ rope dangling over a cliff edge. He could hear the robbers below, so cut their rope and lowered himself down the cliff on his own rope. In his own words, “shinning down a rope at midnight, into a nestful of industrious tomb robbers, is a pastime which at least does not lack excitement”. After what he described laconically as “an awkward moment or two”, the robbers accepted their only option was to leave via Carter’s rope, leaving Carter to spend the next few months clearing the tomb (that of Hatshepsut as consort and so unused). Readers of Elizabeth Peters’ (the pen name of Egyptologist Barbara Mertz) historical mystery novels about the fictional archaeologist Radcliffe Emerson may recognise similarities with Emerson’s exploits in The Hippopotamus Pool (1996). In 1916 Alan Gardiner commissioned Carter to draw the Opet festival reliefs and inscriptions at Luxor temple but sadly his drawings remain unpublished at the Griffith Institute in Oxford. Norman de Garis Davies continued to record the decoration in tombs on the West Bank at Luxor on behalf of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met), until he left for the East to work with the French Red Cross. The Met also excavated Middle and New Kingdom pyramids at Lisht, south of Cairo, and Amenhotep III’s New Kingdom palace at Malkata outside Thebes. Eckley Coxe, the Honorary Secretary of the US branch of the EES, conducted private excavations at Memphis, discovering the palace of Merenptah, and this work was continued by Clarence Fisher for the University of Pennsylvania after Coxe’s death. Fisher was another who combined archaeology and war work – whilst in Egypt he also worked on behalf of the Near East Relief, an American aid program set up in 1915 to provide aid to Armenians after the genocide. This was later merged with the Syrian-Palestine Relief Fund and the Persian War Relief, and eventually provided aid to all those suffering from the crisis, regardless of ethnicity or religion … tragically, the need for such assistance is still with us 100 years later. Further reading/key sources: Bierbrier, M. 2012. Who was who in Egyptology (4th edition, revised). London: Egypt Exploration Society. Drower, M. 1985. Flinders Petrie: A life in Archaeology. London: Gollancz. Egypt Exploration Society Library and Archive James, T G H. 2001. Howard Carter: The path to Tutankhamun. London: I. B. Tauris. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Volumes 2-6 (Balabish) and 50 (obituary of Wainwright) Reeves, N and Taylor, J H. 1992. Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London: British Museum. Wainwright, G A. Balabish. London: Egypt Exploration Society. Petrie Museum exhibition “Different Perspectives” 16 May – 31 October 2017 (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/culture/petrie-museum ) Winstone, H V. 2006. Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. Barzan Publishing. By Susan Biddle (Volunteer, Different Perspectives Project) On 4 August 1914, Flinders Petrie’s diary records “Engelbach, Willey, Gunn all off, training for the war”. But what did these people do in the war? The main focus of my research for the Differing Perspectives exhibition was to investigate whether the skills Flinders Petrie’s students (his “pups”, as they called themselves) acquired while working with him in the field in Egypt proved useful to the military during the war. Although some fieldwork continued in Egypt during the war, the general view was summarised by Emily Paterson, general secretary of the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF). Drawing on EEF correspondence, H. V. F. Winstone recorded that when in 1915 a young man asked to be taken onto a dig team Paterson replied “the EEF has no place on its staff for a young man of 23 who knows several languages, can manage men and obviously if he can 'rough it' on excavations, is fit for military service.” Most of the “pups” of military age did volunteer. One of the oldest pups was Howard Carter, who had worked with Petrie at Amarna in 1891-92. Carter claimed he spent the war in military service, but, aged over 40, he was dismissed in 1915. Before then he carried secret dispatches for the British High Commissioner, and secret messages between the British and French and their Arab contacts such as revolutionaries and deserters from the Ottoman army, and acted as interpreter in military interviews with potential Arab recruits. No doubt his knowledge of the Egyptian language and of Egyptians, acquired over 20 years of work in Egypt, proved useful in all these activities. At least once he may have had a more hands-on role; he is credited with blowing up the German dig house at the Ramesseum which British archaeologists considered “an ugly red abomination emblematic of German pushful vulgarity”: a new use for the experience with explosives Carter had acquired while working with fellow EEF excavator Edouard Naville at Deir el-Bahri. David Randall MacIver provided another example of the transfer of skills from archaeological to military use. He had worked with Petrie from 1898 to 1902, and subsequently excavated in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) and Nubia, and was in no doubt that his archaeological experience could benefit the military. On 27 August 1914 MacIver set out what he perceived as his qualifications, claiming to be “as nearly absolute master of [German] as any Englishman ever is”, “pretty good” at French and Italian, and “quite strong” in Spanish; having commanded large archaeological expeditions, he was used to camp life and transport; and was “in perfect physical condition” owing to his constant outdoor life. His War Office files (WO 33/46265) also note his “fair” horsemanship, ability to speak Egyptian Arabic and Greek, and his topographical knowledge of Germany, France, Belgium, Egypt and the Sudan. He initially served as an interpreter in France with the IEF Ferizepore Brigade HQ, but In November 1915 Field Marshall Sir John French suggested that with his knowledge of the Eastern Mediterranean and linguistic skills MacIver could be more usefully employed there rather than in France. After a crash course to brush up his Greek, MacIver sailed first to Alexandria and then to Salonica where he served as an interpreter. He was promoted from Second Lieutenant to Captain in 1916 and mentioned in despatches in June 1918, before being demobbed in February 1919. Reginald Engelbach, the first assistant named in Petrie’s 4 August diary entry, had trained as an engineer in England but had been sent to Egypt to convalesce in 1909. Having become fascinated with Ancient Egyptian culture, he studied Egyptian, Coptic and Arabic at UCL and worked with Petrie from 1911 to 1914 where his engineering skill proved useful in dealing with water in a pyramid well. He joined the Artists’ Rifles, a volunteer corps popular with recruits from public schools and universities. In January 1915 he was appointed 2nd Lieutenant in the London Electrical Engineers, and subsequently served in France and Gallipoli, and finally was sent by General Edmund Allenby to report on the ancient sites in Syria and Palestine: an early “Monuments Man”. Battiscombe Gunn was another who had trained as an engineer, but preferred Egyptology. Between 1908 and 1911 he worked as a sub-editor of the Continental Daily Mail in Paris, as a result of which he spoke French fluently, and had also studied Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Arabic. He didn’t have much time to put his skills to military use before being invalided out of the Territorials in 1915. The third student named by Petrie, Rupert Duncan Willey had studied Hebrew, Sanscrit and Arabic and first worked with Petrie in the final pre-War season at Lahun, when they found the spectacular “Lahun treasure”. Although most of this treasure is now in the New York Metropolitan Museum, a few pieces are held by the Petrie Museum. Willey joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, but in May 1915 Sir Percy Cox requested his transfer to the Political and Administrative Staff employed by the India Office. Willey was granted the temporary rank of Captain (but sadly without the pay or allowances for that rank) in March 1918 and was mentioned in despatches “for distinguished and gallant services and devotion to duty” by the Commander in Chief of the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force in February 1919. He continued to serve as Assistant Political Officer in South Kurdistan after the war but in 1919 was assassinated in Amara by Kurds assisted by local police in an incident straight from “Boy’s Own”. Willey was stabbed in bed; a fellow officer attempted to shoot the assassins and ultimately jumped to his death through the window, taking two of his assailants with him. All brave men, who didn’t hesitate to offer their skills in the service of their country. Further reading/key sources:

Bierbrier, M. 2012. Who was who in Egyptology (4th edition, revised). London: Egypt Exploration Society. Egypt Exploration Society Library and Archive Drower, M. 1985. Flinders Petrie: A life in Archaeology. London: Gollancz. Fieldhouse, D. 2002. Kurds, Arabs and Britons: The Memoir of Col W A Lyon in Kurdistan 1918-1945. London: I B Tauris. James, T G H. 2001. Howard Carter: The path to Tutankhamun. London: I. B. Tauris. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Petrie Museum exhibition “Different Perspectives” 16 May – 31 October 2017 Reeves, N and Taylor, J H. 1992. Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London: British Museum. Summers, D. Caius World War I Centenary Commemoration, part of the War Memorial Biographies project of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge (Willey) (available in the Chapel at Gonville & Caius College) War office records at The National Archives, Kew WO 33/46265 (MacIver) and WO 374/74635 (Willey) Winstone, H V. 2006. Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. Barzan Publishing. |

Categories

All

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed