|

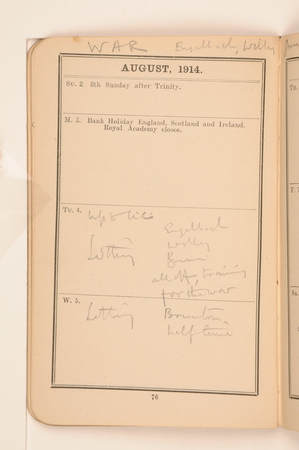

By Susan Biddle (Volunteer, Different Perspectives Project) On 4 August 1914, Flinders Petrie’s diary records “Engelbach, Willey, Gunn all off, training for the war”. But what did these people do in the war? The main focus of my research for the Differing Perspectives exhibition was to investigate whether the skills Flinders Petrie’s students (his “pups”, as they called themselves) acquired while working with him in the field in Egypt proved useful to the military during the war. Although some fieldwork continued in Egypt during the war, the general view was summarised by Emily Paterson, general secretary of the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF). Drawing on EEF correspondence, H. V. F. Winstone recorded that when in 1915 a young man asked to be taken onto a dig team Paterson replied “the EEF has no place on its staff for a young man of 23 who knows several languages, can manage men and obviously if he can 'rough it' on excavations, is fit for military service.” Most of the “pups” of military age did volunteer. One of the oldest pups was Howard Carter, who had worked with Petrie at Amarna in 1891-92. Carter claimed he spent the war in military service, but, aged over 40, he was dismissed in 1915. Before then he carried secret dispatches for the British High Commissioner, and secret messages between the British and French and their Arab contacts such as revolutionaries and deserters from the Ottoman army, and acted as interpreter in military interviews with potential Arab recruits. No doubt his knowledge of the Egyptian language and of Egyptians, acquired over 20 years of work in Egypt, proved useful in all these activities. At least once he may have had a more hands-on role; he is credited with blowing up the German dig house at the Ramesseum which British archaeologists considered “an ugly red abomination emblematic of German pushful vulgarity”: a new use for the experience with explosives Carter had acquired while working with fellow EEF excavator Edouard Naville at Deir el-Bahri. David Randall MacIver provided another example of the transfer of skills from archaeological to military use. He had worked with Petrie from 1898 to 1902, and subsequently excavated in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) and Nubia, and was in no doubt that his archaeological experience could benefit the military. On 27 August 1914 MacIver set out what he perceived as his qualifications, claiming to be “as nearly absolute master of [German] as any Englishman ever is”, “pretty good” at French and Italian, and “quite strong” in Spanish; having commanded large archaeological expeditions, he was used to camp life and transport; and was “in perfect physical condition” owing to his constant outdoor life. His War Office files (WO 33/46265) also note his “fair” horsemanship, ability to speak Egyptian Arabic and Greek, and his topographical knowledge of Germany, France, Belgium, Egypt and the Sudan. He initially served as an interpreter in France with the IEF Ferizepore Brigade HQ, but In November 1915 Field Marshall Sir John French suggested that with his knowledge of the Eastern Mediterranean and linguistic skills MacIver could be more usefully employed there rather than in France. After a crash course to brush up his Greek, MacIver sailed first to Alexandria and then to Salonica where he served as an interpreter. He was promoted from Second Lieutenant to Captain in 1916 and mentioned in despatches in June 1918, before being demobbed in February 1919. Reginald Engelbach, the first assistant named in Petrie’s 4 August diary entry, had trained as an engineer in England but had been sent to Egypt to convalesce in 1909. Having become fascinated with Ancient Egyptian culture, he studied Egyptian, Coptic and Arabic at UCL and worked with Petrie from 1911 to 1914 where his engineering skill proved useful in dealing with water in a pyramid well. He joined the Artists’ Rifles, a volunteer corps popular with recruits from public schools and universities. In January 1915 he was appointed 2nd Lieutenant in the London Electrical Engineers, and subsequently served in France and Gallipoli, and finally was sent by General Edmund Allenby to report on the ancient sites in Syria and Palestine: an early “Monuments Man”. Battiscombe Gunn was another who had trained as an engineer, but preferred Egyptology. Between 1908 and 1911 he worked as a sub-editor of the Continental Daily Mail in Paris, as a result of which he spoke French fluently, and had also studied Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Arabic. He didn’t have much time to put his skills to military use before being invalided out of the Territorials in 1915. The third student named by Petrie, Rupert Duncan Willey had studied Hebrew, Sanscrit and Arabic and first worked with Petrie in the final pre-War season at Lahun, when they found the spectacular “Lahun treasure”. Although most of this treasure is now in the New York Metropolitan Museum, a few pieces are held by the Petrie Museum. Willey joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, but in May 1915 Sir Percy Cox requested his transfer to the Political and Administrative Staff employed by the India Office. Willey was granted the temporary rank of Captain (but sadly without the pay or allowances for that rank) in March 1918 and was mentioned in despatches “for distinguished and gallant services and devotion to duty” by the Commander in Chief of the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force in February 1919. He continued to serve as Assistant Political Officer in South Kurdistan after the war but in 1919 was assassinated in Amara by Kurds assisted by local police in an incident straight from “Boy’s Own”. Willey was stabbed in bed; a fellow officer attempted to shoot the assassins and ultimately jumped to his death through the window, taking two of his assailants with him. All brave men, who didn’t hesitate to offer their skills in the service of their country. Further reading/key sources:

Bierbrier, M. 2012. Who was who in Egyptology (4th edition, revised). London: Egypt Exploration Society. Egypt Exploration Society Library and Archive Drower, M. 1985. Flinders Petrie: A life in Archaeology. London: Gollancz. Fieldhouse, D. 2002. Kurds, Arabs and Britons: The Memoir of Col W A Lyon in Kurdistan 1918-1945. London: I B Tauris. James, T G H. 2001. Howard Carter: The path to Tutankhamun. London: I. B. Tauris. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Petrie Museum exhibition “Different Perspectives” 16 May – 31 October 2017 Reeves, N and Taylor, J H. 1992. Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London: British Museum. Summers, D. Caius World War I Centenary Commemoration, part of the War Memorial Biographies project of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge (Willey) (available in the Chapel at Gonville & Caius College) War office records at The National Archives, Kew WO 33/46265 (MacIver) and WO 374/74635 (Willey) Winstone, H V. 2006. Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. Barzan Publishing.

Arthur farrow

15/2/2018 21:43:33

A fascinating read, splendidly researched.. i would love to know more of the relationship between Howard Carter and Battiscombe Gunn, as each counted the other a firm friend. By the reports of those who knew, and worked, with him, Carter was not an adept at forming, and espcially maintaining, relationships. Alan Gardiner, for whom Carter had little regard, tactfully referred to Carter as 'not the most tractable fo men', although he went to say that he was 'little short of a genius in the practical matters of excavation'. Gunn and Carter were drawn to each other because they shared a similar background, outside the university educated, upper class elite. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed