History of Archaeology

|

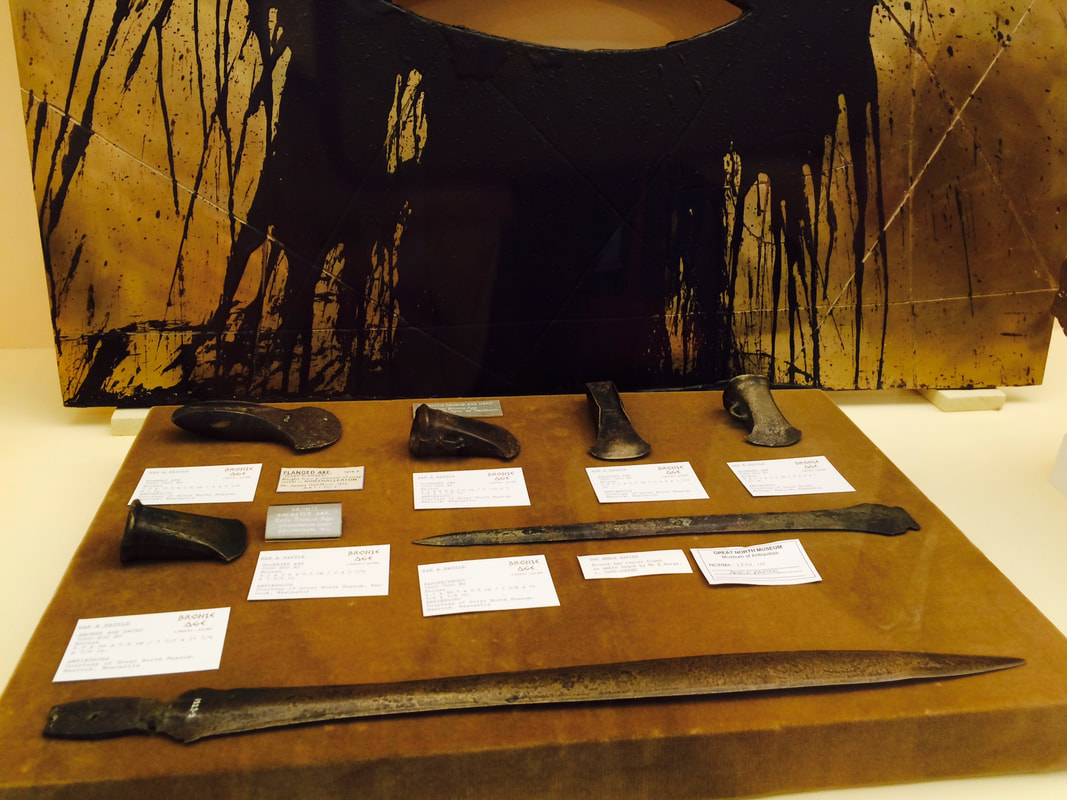

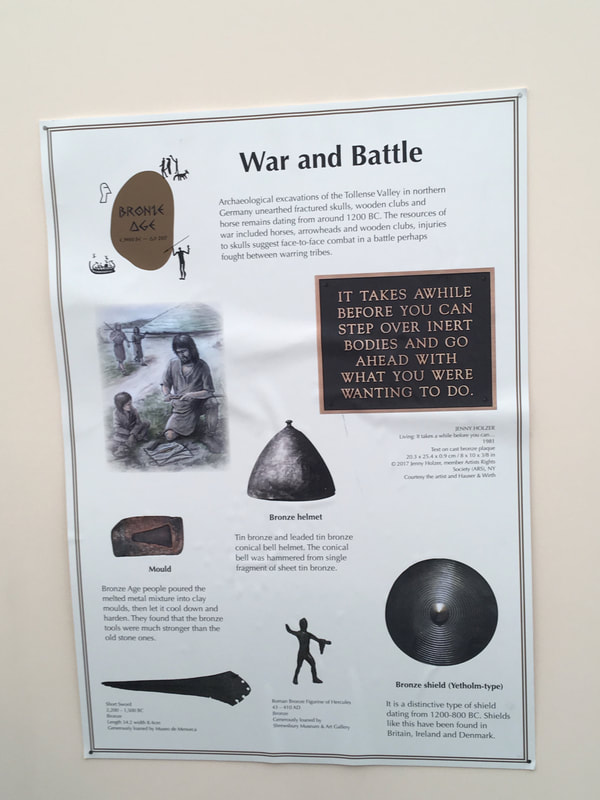

How Hauser & Wirth put traditional museum display and practice under scrutiny at Frieze London 2017 By Dr Neil Wilkin (The British Museum) Once, at a New Year’s Eve party in South London, I was introduced by a tipsy friend as the ‘Curator of Bronze at the British Museum’. What, all bronze? From all over the world? For all time? Gee, is that a thing? ‘As it happens, I curate the British and European Bronze Age collection...from about 5,000 years ago to about 3,000 years ago….dates vary across Europe depending on the spread of the first metallurgy and on whether we are talking about the Copper Age (the Chalcolithic) or Bronze Age ‘proper’ when copper was mixed with tin to form…’ By the time I’d issued that sober corrective the bells had well and truly tolled. Until recently, mention of the Bronze Age was not on any school curriculum and its common for even the best-read to ask whether iron came before or after bronze - one rusts like hell after all. And even if you do know when it was, why is it important to describe what it was with reference to an inert lump of metal? Have we dozed through Sociology and History straight into Chemistry? Would ‘banking age’, ‘digital age’, ‘Internet age’, sum up the complexity, the highs and lows of your life, today? But these are old arguments, well rehearsed. It was intriguing, then, to read that Professor Mary Beard from University of Cambridge was to collaborate with the contemporary and modern gallery Hauser & Wirth to create a booth entitled ‘BRONZE AGE c. 3500 BC – AD 2017’ at Frieze London. For the uninitiated, Frieze London is an international contemporary art fair held every October in Regent’s Park. It's formed of many individual gallery booths housed within a village of temporary tents that belie the huge wealth and money making potential of modern art. Not everyone is a fan. A spectacularly gruesome review of last year's fair by Keith Miller was titled, ‘How Frieze eats the soul’ and describes the whole event as a ‘travesty of everything art should be, devoid of any joy or freedom, of any true call to inquisitiveness or critical thought’ . It’s all the more notable, then, that Mary Beard has collaborated with Hauser & Wirth, a blue-chip art gallery. Unlike most, they have pursued a thematic approach to their Frieze booth for the last two years. Last year the artist’s studio, this year an imaginary (‘fictional’, ‘forgotten’) museum. The colour palette is immediately suggestive of a museum out of time: cream, beige and brown framed by varnished wood and plenty of reflective glass and perspex. There are some nice touches. The museum’s old heavy wooden doors have small glass panes and are the kind that either swing back to reveal our most formative memories or waft us away with a skelp. Other props evoke time and place: a red fire bucket and retro extinguisher, framed line drawings of archaeological monuments and artefact catalogues cover the walls in tight rows. A humidity monitor has the protective plastic screen still attached, appropriately faux numbers appearing on its face. A temporary removal slip notes that one object has been lent to the British Museum. Finally, a gift-shop sells rubbers and leather bookmarks of the type purchased on every school trip since the Bronze Age. The revenue from this shop reportedly raised £10,000 in donations for UK regional museums, which we should applaud while simultaneously averting our eyes from the eye-watering price tags of the works sold by Hauser & Wirth; one sculpture by Hans Arp sold for $1.1m during the fair. Bronze as an enduring medium for art has already been explored by a major Royal Academy show in 2012. That exhibition explored how artists and craftspeople have manipulated the physical properties and qualities of bronze to create masterpieces for 5,000 years. Hauser & Wirth’s display cannot fairly be considered in the same breath but the contrast is informative: rather than focus on the materiality of bronze, they bring together an unexpected and sometimes unremarkable range of objects of different dates, periods and kinds. Some are average museum fare: axes and tools from Bronze Age hoards that are to be found in most regional and national museums across Britain. Others are are staples of more conventional Frieze and Frieze Masters displays, including work by Louise Bourgeois and Henry Moore. The added value comes from the juxtaposition of these objects which is achieved primarily through the tricks and tropes of museum presentation. Mary Beard’s involvement and intervention provides a compelling edge. She facilitated loans from several regional UK and international museums and ‘plays’ the part of the expert curator. The results are not mere whimsy. The ‘themes’ explored in the interpretation panels: ‘Domestic Life’; ‘Fertility and the body’; ‘Religion and burial’; ‘Decoration and adornment’; ‘War and battle’, largely echo those of the British Museum’s European Bronze Age displays in Gallery 51. The text of each is short and clear but the overall tone is over-cautious and stereotyped: ‘Pots were being made for all different purposes…’ ‘Bronze Age metalsmiths made beautiful jewellery from bronze age gold.’ This knowing blandness is strangely reassuring in our over-complex world. But the satire is fair. My own attempts to bring the Bronze Age to the widest possible audience have often centred on similar themes, and many of the stock phrases, ideas and narratives they contain. There was an immediate flinch of embarrassment that gave way to a catharsis of sorts. Let’s think and talk and act on the narratives that recur ad nauseum, let’s look for better ways of telling our stories and let’s look with fresh eyes. On occasion contemporary works are featured on the panels alongside ancient ones, continuing the strategy of blurring modern/ancient boundaries. An image of the Venus of Willendorf appears on the panel for the ‘Fertility and the body’ theme where it is described as a ‘Bronze Age fertility goddess’. This is only inaccurate by about 20,000 years. Anachronistic playfulness of this sort can be fun but it is certainly not new. Ice Age Art (curated by the British Museum’s Jill Cook in 2013) cleverly combined masterpieces from deep history with modern works by the likes of Henry Moore and Matisse to make far more powerful and interesting points about humanity by juxtaposing objects of ‘archaeology’ and ‘art’. The digital element of the display is particularly generous: an audio guide that can be downloaded via iTunes, films of Beard discussing objects playing on rotation in the gallery and on a dedicated exhibition website and a slick online catalogue, all of which have an amusing authenticity. The book cases behind Beard in the films are reminiscent of those featured in the British Museum’s recent ‘Curators Corner’ series on YouTube. In one audio guide entry, ‘Unknown Axe’, Beard discusses a humble Late Bronze Age socketed axe borrowed from the Great North Museum in Newcastle. She rightly points out that these were ‘everyday’ objects and that ‘nothing could have looked more ordinary’ (to Bronze Age people). Each year metal detectorists find hundreds of similar objects across England and in the British Museum stores there are drawers upon drawers. For Beard, archaeologists are akin to artists because they fill museum cases with objects that ‘just happen to be very old’ for us to admire. Perhaps, but this does seem like a gross simplification of what both artists and archaeologists can do. Perhaps more interesting is what’s known but unsaid about this ‘unknown’ object: that it’s likely to reflect a particular regional identity and that by using the latest technologies it is possible to tell what the axe was used for, and that by studying the context of its deposition it is possible to explore its cultural and religious symbolism. There is no reason for Beard, a Classicist by profession, to know this, but there is a need for archaeologists and curators to better communicate their knowledge and ideas. In another audioguide entry, Beard discusses Subodh Gupta’s bronze potatoes, connecting them to a sadistic joke played by Roman emperors inviting lower status dinner guests to feasts then presenting them with artificial food so that they could only watch on while their masters gorged on the real thing. With tickets for Frieze selling for £40, the story is certainly prescient, not least for the local museum curators and archaeologists fortunate enough to find themselves at Frieze London 2017. The collaboration has been described by Beard a satire and there is certainly fun and humour. But at times it can feel like an in-joke that employs the aesthetic of the underfunded public museum to promote the intellectual calibre of a very successful private gallery. There’s something rather ill judged about the head of the gallery’s senior director, Neil Wenman, being minted on a specially made hoard of coins displayed in a healthy pile at the centre of a large bronze bowl. There are other uneasy elements. When reproduced images appear on gallery panels there are copyright captions for the contemporary work but not for museum objects or photographs and reconstruction drawings of archaeological sites. This reflects an important disparity between the successful commercialisation of modern art galleries and the debates that still surround how museums can and should charge for image use. Hauser & Wirth also make much of the inclusion of eBay purchases ‘masquerading’ as archaeological finds. Of course many ‘real’ archaeological finds do end up on eBay, even in Britain, where our standards of archaeological recording and retention of finds in museum collections is world leading. Finds made by metal detectorists can be legitimately sold and bought if they do not qualify as Treasure under the stipulations of the Treasure Act (1996) and Designation Order (2002), or if museum acquisition isn’t desirable or financially viable.

To really understand what the display is satirising, we need to go back to the groundbreaking work of 19th century archaeologist Christian Jurgensen Thomsen’s ‘Three Age System’. Without any of the benefit of modern scientific dating techniques, Thomsen was able to define a tripartite division of time: first there were artefacts of stone, then bronze and then iron. The framework was quickly refined into many more sub-divisions of time across Europe, helping to create the very structure of knowledge about what happened in a period without writing. Only since the advent of reliable scientific dating techniques in the 1990s have we been freed from the system of inferences that Thomsen bequeathed us. It is easy to forget how fundamental and ingrained the system became. If it still casts its shadow across archaeology and underfunded museums it is hardly surprising but it is important that academic and curators begin the process of telling new, more inventive and liberated stories about this period of time: the stories of the people behind the jargon. I left Hauser & Wirth’s booth with mixed emotions but full of thoughts. It evoked memories of my local museum from childhood and the underfunded and fossilised galleries that are all too common today. These institutions evoke a pang of sadness mixed with nostalgia. But the narratives that are rightly satirised by Beard et al. are not the preserve of local museums alone, they are also present in nationals and in the headline stories we still tell the public. New and better narratives are clearly needed. Careful thought must be given to maintaining the kinesthetic ‘life’ that old museum displays and designs provoke and to the transportive and disruptive power of nostalgia. But while we are still busy reflecting, Hauser & Wirth will be planning next October’s aesthetic conceit, perhaps another fig leaf on the hyper-commercialisation of the contemporary art world. Let us hope they’ll rise to their own challenge, turning the mirror back on themselves and on Frieze itself. 'BRONZE AGE c. 3500 BC – AD 2017', Hauser & Wirth, Booth D10, was at Frieze London, Regent’s Park, October 5-8, 2017. It will be re-staged at FirstSite, Colchester, from November, 2017. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed