History of Archaeology

|

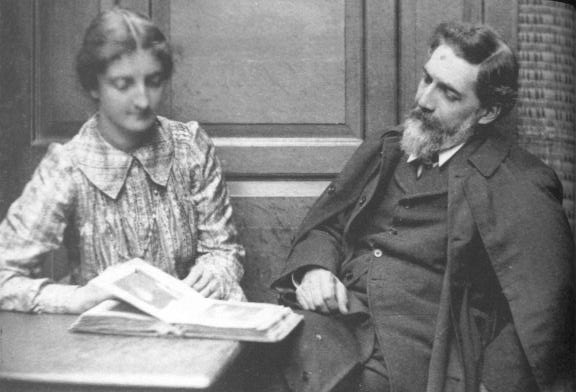

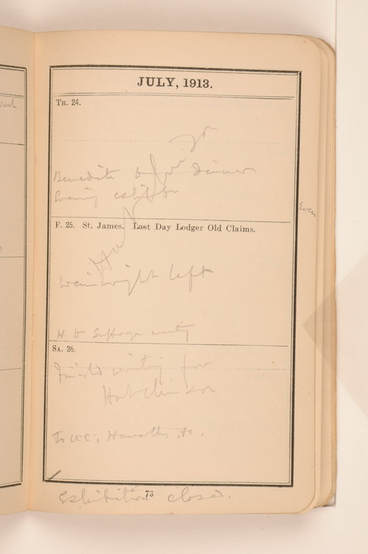

By Dr Debbie Challis (LSE Library) After ten years working in public engagement at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology UCL I left for all things in political, social and economic science at LSE Library. LSE Library holds, among other archives, the Women’s Library, which has the largest collection of material relating to women’s history, particularly the campaign for female suffrage, in the UK. My former colleague Alice Stevenson wondered if there was anything relating to Hilda Petrie (nee Urlin) in The Women’s Library @ LSE archives. I searched and duly found a letter from Flinders Petrie dated 20 June 1912 referring to his wife’s current illness and then her inability to take on any more work for the London Society for Women’s Suffrage (LSWS) as she would be too busy working for him.* It is, perhaps, darkly ironic that Petrie refuses activist or campaigning work for women’s suffrage on behalf of his wife as he was reliant on her skills with subscribers. It does suggest though that Flinders Petrie was largely supportive of his wife’s (and his colleagues’ and students’) involvement in the campaign for women to have the vote. However, to find Hilda’s voice one has to dig a little deeper in the archives and explore the context of her involvement more fully. In his 1912 letter Flinders Petrie is writing to Philippa Strachey, the secretary of the LWSS, who was, like her mother Lady Jane Strachey and sister Ray Strachey, an ardent suffragist.** The London Society for Women’s Suffrage (LSWS) was affiliated to the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the largest such society in the UK with 4,000 paying members by 1912. It and other suffragist societies followed law abiding means of campaigning – petitions, speeches, processions – not the militant tactics used by suffragettes in the Women’s Social and Political Union (1903) or the Women’s Freedom League (1907). Women and some men in suffragist organisations had been formally campaigning for the vote since the 1860s but had become more formally organised in 1897. In the summer of 1912 Flinders Petrie may not have approved of the NUWSS since their leader Millicent Garrett Fawcett was urging support for the Labour Party as the only political party supporting women’s suffrage, an action that divided suffragists. Many felt that the NUWSS should remain 'non-party' and kept out of partisan politics, let alone make links with socialists whom many feared were dangerous radicals. Flinders Petrie was a member of the Anti-Socialist Society. However, it is likely that he needed all assistance with his exhibition at University College London of finds from the British School of Archaeology in Egypt’s season at Kafr Ammar and Heliopolis. As Amara Thornton notes the exhibition was fundamental for Petrie's fundraising due to the system of 'partage' - dividing objects between subscribers - that was then in place. This letter reveals how reliant Flinders Petrie was on his wife Hilda in this process. From the time of her marriage to Flinders Petrie in 1897, Hilda worked as a fundraiser for the excavations in Egypt and later Palestine until the late 1930s, which has been well documented by Margaret Drower and Rachael Sparks. Her charm was legendary and she wrote to all subscribers personally as well as arranging public lectures and writing articles for popular magazines, as Sparks has shown. Whether she was fundraising for the suffragists is, as yet, unclear but Petrie’s pocket diaries occasionally records Hilda’s attendance at suffrage meetings, such as this entry from 25 July 1913. It is an important entry as the next day was the large rally of suffragists in Hyde Park after their month of a Great Pilgrimage from all parts of the country. This was in an attempt to be heard by the Liberal government and to change public opinion of women campaigning for the vote; arguably militant suffragette violence, such as arson, had undermined the campaign and image of women seeking the vote.

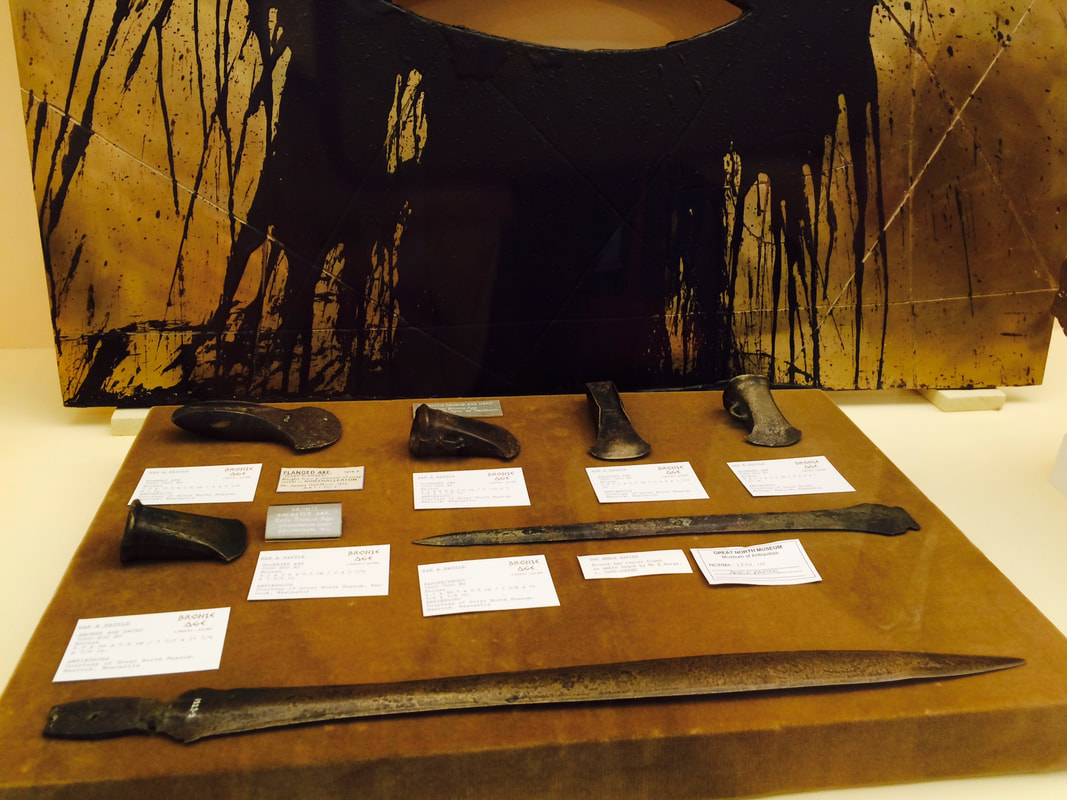

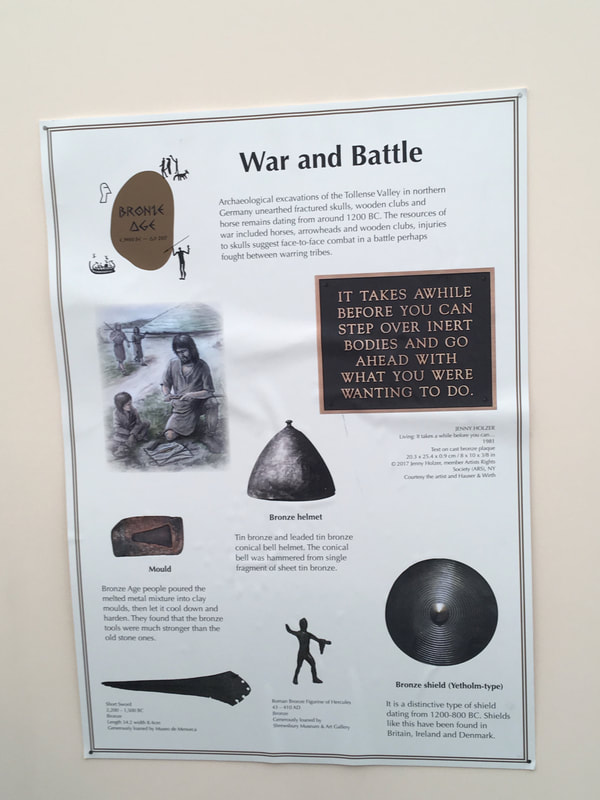

More work digging in the archives (in meeting minutes during the 1910s, for example) is needed to fully ascertain the role of Hilda in the suffragist campaign. Her role may have been limited due to the time spent outside of the country on excavations. Certainly many of her circle were involved in the campaign for female suffrage as well as writing in journals and giving lectures - public engagement for the cause that Hilda would later carry out for Egyptology and the BSAE. For example, Hilda’s friend Beatrice Orme was sister to Eliza, the first woman to obtain a LLB (law degree) from the University of London and an early member of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage (a forerunner of the LSWS). Eliza wrote on practical solutions to problems for women and argued for education and independence for women in popular journals. By the time Eliza and Beatrice were living together in Tulse Hill in the late 1890s, Beatrice was also attending excavations in Egypt with Hilda. Margaret Drower mentions that 'suffragette Philippa Fawcett' was one of Hilda’s neighbours and ‘idols’ when growing up. Philippa was daughter of NUWSS president Millicent Garrett Fawcett and became a senior wrangler in Mathematics at Cambridge, but could not be awarded the scholarship due to being a woman. She wrote once for a suffragette journal but, like her mother, was a suffragist. We can surmise Hilda’s involvement and beliefs from those of her friends and acquaintances but her involvement in the women's movement is more clear and well documented through her activities during the First World War. To be continued... References/Further Reading Crawford, E. 1999. The Women’s Suffrage Movement. Reference Guide 1866 – 1928, London: Taylor & Francis / UCL Press. Drower, M. 1985. Flinders Petrie: A Life in Archaeology. London: Gollancz. Howsam, L. ‘Orme, Eliza (1848–1937)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/37825: Published in print: 23 September 2004, online: 23 September 2004. Petrie, William Matthew Flinders, Letter to Philippa Strachey, dated 20 June 1912, The Women’s Library @ LSE, Autograph Letter Collection: 9/01/1002 Sparks, R.2013. PUBLICISING PETRIE: Financing Fieldwork in British Mandate Palestine (1926–1938). Present Pasts 5(1), p.Art. 2. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/pp.56 Thornton, A. 2015. Exhibition Season: Annual Archaeological Exhibitions in London, 1880s-1930s. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 25 (1)p.Art.2: DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/bha.252 *20 June 1912 Dear Madam, I regret to say that Mrs Petrie is obliged to take entire rest at present as she has been unwell lately; and she has a very tiring month before her of daily attention to subscribers at the Exhibition of the British School of Archaeology, the whole personal detail of which is in her hands. She will therefore be unable to undertake anything else until the end of July. I write as she is away for entire rest. Yours truly, Wm. F. Petrie **Her brother was Lytton Strachey, member of the Bloomsbury Group and author of the caustic Eminent Victorians. How Hauser & Wirth put traditional museum display and practice under scrutiny at Frieze London 2017 By Dr Neil Wilkin (The British Museum) Once, at a New Year’s Eve party in South London, I was introduced by a tipsy friend as the ‘Curator of Bronze at the British Museum’. What, all bronze? From all over the world? For all time? Gee, is that a thing? ‘As it happens, I curate the British and European Bronze Age collection...from about 5,000 years ago to about 3,000 years ago….dates vary across Europe depending on the spread of the first metallurgy and on whether we are talking about the Copper Age (the Chalcolithic) or Bronze Age ‘proper’ when copper was mixed with tin to form…’ By the time I’d issued that sober corrective the bells had well and truly tolled. Until recently, mention of the Bronze Age was not on any school curriculum and its common for even the best-read to ask whether iron came before or after bronze - one rusts like hell after all. And even if you do know when it was, why is it important to describe what it was with reference to an inert lump of metal? Have we dozed through Sociology and History straight into Chemistry? Would ‘banking age’, ‘digital age’, ‘Internet age’, sum up the complexity, the highs and lows of your life, today? But these are old arguments, well rehearsed. It was intriguing, then, to read that Professor Mary Beard from University of Cambridge was to collaborate with the contemporary and modern gallery Hauser & Wirth to create a booth entitled ‘BRONZE AGE c. 3500 BC – AD 2017’ at Frieze London. For the uninitiated, Frieze London is an international contemporary art fair held every October in Regent’s Park. It's formed of many individual gallery booths housed within a village of temporary tents that belie the huge wealth and money making potential of modern art. Not everyone is a fan. A spectacularly gruesome review of last year's fair by Keith Miller was titled, ‘How Frieze eats the soul’ and describes the whole event as a ‘travesty of everything art should be, devoid of any joy or freedom, of any true call to inquisitiveness or critical thought’ . It’s all the more notable, then, that Mary Beard has collaborated with Hauser & Wirth, a blue-chip art gallery. Unlike most, they have pursued a thematic approach to their Frieze booth for the last two years. Last year the artist’s studio, this year an imaginary (‘fictional’, ‘forgotten’) museum. The colour palette is immediately suggestive of a museum out of time: cream, beige and brown framed by varnished wood and plenty of reflective glass and perspex. There are some nice touches. The museum’s old heavy wooden doors have small glass panes and are the kind that either swing back to reveal our most formative memories or waft us away with a skelp. Other props evoke time and place: a red fire bucket and retro extinguisher, framed line drawings of archaeological monuments and artefact catalogues cover the walls in tight rows. A humidity monitor has the protective plastic screen still attached, appropriately faux numbers appearing on its face. A temporary removal slip notes that one object has been lent to the British Museum. Finally, a gift-shop sells rubbers and leather bookmarks of the type purchased on every school trip since the Bronze Age. The revenue from this shop reportedly raised £10,000 in donations for UK regional museums, which we should applaud while simultaneously averting our eyes from the eye-watering price tags of the works sold by Hauser & Wirth; one sculpture by Hans Arp sold for $1.1m during the fair. Bronze as an enduring medium for art has already been explored by a major Royal Academy show in 2012. That exhibition explored how artists and craftspeople have manipulated the physical properties and qualities of bronze to create masterpieces for 5,000 years. Hauser & Wirth’s display cannot fairly be considered in the same breath but the contrast is informative: rather than focus on the materiality of bronze, they bring together an unexpected and sometimes unremarkable range of objects of different dates, periods and kinds. Some are average museum fare: axes and tools from Bronze Age hoards that are to be found in most regional and national museums across Britain. Others are are staples of more conventional Frieze and Frieze Masters displays, including work by Louise Bourgeois and Henry Moore. The added value comes from the juxtaposition of these objects which is achieved primarily through the tricks and tropes of museum presentation. Mary Beard’s involvement and intervention provides a compelling edge. She facilitated loans from several regional UK and international museums and ‘plays’ the part of the expert curator. The results are not mere whimsy. The ‘themes’ explored in the interpretation panels: ‘Domestic Life’; ‘Fertility and the body’; ‘Religion and burial’; ‘Decoration and adornment’; ‘War and battle’, largely echo those of the British Museum’s European Bronze Age displays in Gallery 51. The text of each is short and clear but the overall tone is over-cautious and stereotyped: ‘Pots were being made for all different purposes…’ ‘Bronze Age metalsmiths made beautiful jewellery from bronze age gold.’ This knowing blandness is strangely reassuring in our over-complex world. But the satire is fair. My own attempts to bring the Bronze Age to the widest possible audience have often centred on similar themes, and many of the stock phrases, ideas and narratives they contain. There was an immediate flinch of embarrassment that gave way to a catharsis of sorts. Let’s think and talk and act on the narratives that recur ad nauseum, let’s look for better ways of telling our stories and let’s look with fresh eyes. On occasion contemporary works are featured on the panels alongside ancient ones, continuing the strategy of blurring modern/ancient boundaries. An image of the Venus of Willendorf appears on the panel for the ‘Fertility and the body’ theme where it is described as a ‘Bronze Age fertility goddess’. This is only inaccurate by about 20,000 years. Anachronistic playfulness of this sort can be fun but it is certainly not new. Ice Age Art (curated by the British Museum’s Jill Cook in 2013) cleverly combined masterpieces from deep history with modern works by the likes of Henry Moore and Matisse to make far more powerful and interesting points about humanity by juxtaposing objects of ‘archaeology’ and ‘art’. The digital element of the display is particularly generous: an audio guide that can be downloaded via iTunes, films of Beard discussing objects playing on rotation in the gallery and on a dedicated exhibition website and a slick online catalogue, all of which have an amusing authenticity. The book cases behind Beard in the films are reminiscent of those featured in the British Museum’s recent ‘Curators Corner’ series on YouTube. In one audio guide entry, ‘Unknown Axe’, Beard discusses a humble Late Bronze Age socketed axe borrowed from the Great North Museum in Newcastle. She rightly points out that these were ‘everyday’ objects and that ‘nothing could have looked more ordinary’ (to Bronze Age people). Each year metal detectorists find hundreds of similar objects across England and in the British Museum stores there are drawers upon drawers. For Beard, archaeologists are akin to artists because they fill museum cases with objects that ‘just happen to be very old’ for us to admire. Perhaps, but this does seem like a gross simplification of what both artists and archaeologists can do. Perhaps more interesting is what’s known but unsaid about this ‘unknown’ object: that it’s likely to reflect a particular regional identity and that by using the latest technologies it is possible to tell what the axe was used for, and that by studying the context of its deposition it is possible to explore its cultural and religious symbolism. There is no reason for Beard, a Classicist by profession, to know this, but there is a need for archaeologists and curators to better communicate their knowledge and ideas. In another audioguide entry, Beard discusses Subodh Gupta’s bronze potatoes, connecting them to a sadistic joke played by Roman emperors inviting lower status dinner guests to feasts then presenting them with artificial food so that they could only watch on while their masters gorged on the real thing. With tickets for Frieze selling for £40, the story is certainly prescient, not least for the local museum curators and archaeologists fortunate enough to find themselves at Frieze London 2017. The collaboration has been described by Beard a satire and there is certainly fun and humour. But at times it can feel like an in-joke that employs the aesthetic of the underfunded public museum to promote the intellectual calibre of a very successful private gallery. There’s something rather ill judged about the head of the gallery’s senior director, Neil Wenman, being minted on a specially made hoard of coins displayed in a healthy pile at the centre of a large bronze bowl. There are other uneasy elements. When reproduced images appear on gallery panels there are copyright captions for the contemporary work but not for museum objects or photographs and reconstruction drawings of archaeological sites. This reflects an important disparity between the successful commercialisation of modern art galleries and the debates that still surround how museums can and should charge for image use. Hauser & Wirth also make much of the inclusion of eBay purchases ‘masquerading’ as archaeological finds. Of course many ‘real’ archaeological finds do end up on eBay, even in Britain, where our standards of archaeological recording and retention of finds in museum collections is world leading. Finds made by metal detectorists can be legitimately sold and bought if they do not qualify as Treasure under the stipulations of the Treasure Act (1996) and Designation Order (2002), or if museum acquisition isn’t desirable or financially viable.

To really understand what the display is satirising, we need to go back to the groundbreaking work of 19th century archaeologist Christian Jurgensen Thomsen’s ‘Three Age System’. Without any of the benefit of modern scientific dating techniques, Thomsen was able to define a tripartite division of time: first there were artefacts of stone, then bronze and then iron. The framework was quickly refined into many more sub-divisions of time across Europe, helping to create the very structure of knowledge about what happened in a period without writing. Only since the advent of reliable scientific dating techniques in the 1990s have we been freed from the system of inferences that Thomsen bequeathed us. It is easy to forget how fundamental and ingrained the system became. If it still casts its shadow across archaeology and underfunded museums it is hardly surprising but it is important that academic and curators begin the process of telling new, more inventive and liberated stories about this period of time: the stories of the people behind the jargon. I left Hauser & Wirth’s booth with mixed emotions but full of thoughts. It evoked memories of my local museum from childhood and the underfunded and fossilised galleries that are all too common today. These institutions evoke a pang of sadness mixed with nostalgia. But the narratives that are rightly satirised by Beard et al. are not the preserve of local museums alone, they are also present in nationals and in the headline stories we still tell the public. New and better narratives are clearly needed. Careful thought must be given to maintaining the kinesthetic ‘life’ that old museum displays and designs provoke and to the transportive and disruptive power of nostalgia. But while we are still busy reflecting, Hauser & Wirth will be planning next October’s aesthetic conceit, perhaps another fig leaf on the hyper-commercialisation of the contemporary art world. Let us hope they’ll rise to their own challenge, turning the mirror back on themselves and on Frieze itself. 'BRONZE AGE c. 3500 BC – AD 2017', Hauser & Wirth, Booth D10, was at Frieze London, Regent’s Park, October 5-8, 2017. It will be re-staged at FirstSite, Colchester, from November, 2017. By Dr Jamie Larkin (Birkbeck) The history of museums has recently begun to garner increasing academic attention. While this is welcome, the focus of such intellectual enquiry has tended to rest with the evolution of collections and nature of exhibitionary practices. As yet, little attention has been given over to considering the development of the museum in an operational capacity. Examining the managerial, bureaucratic, commercial and histories of museums can help shed light their institutional development, specifically how their production of culture related to wider social contexts. This post outlines the development of museum postcards as a way for museums to spread knowledge of their collections, but also the nascent commercialism their sale helped inaugurate. Having changed little terms of form or content in the 100+ years since they were first introduced museum postcards are a particularly interesting subject of enquiry; a museum-goer in 1900 would have no problem recognising and using postcards sold in the British Museum today. While this post can only provide a brief overview, museum postcards provide us with a relatively static cultural form with which we can trace attitudes across time. As such there is great scope to consider various cultural and economic facets of museum development through these objects. Background The postcard was first introduced in Austria in 1869, and in the UK the following year. Its early form consisted of a blank card on which a short message could be written on one side, along with the recipient’s address. The postcard revolutionised forms of communication in the mid-to-late 19th century: it turned the formal and expensive tradition of letter writing into a system by which people could correspond more causally and cheaply. The popularity was evident in that 575,000 postcards were sent on their first day of sale (Staff, 1966: 48). These early postcards were primarily produced by the Post Office and thus regulated by the state. However, towards the end of the 19th century regulations were loosened and private stationery firms entered the market. These firms saw potential in the gradual changes that the form of postcards were undergoing. In the 1890s ‘Pictorial Postcards’ were introduced with an image on the front (e.g. an exotic location/famous landmark) and space for writing on the reverse. The novelty and cheapness of sharing visual images resulted in a massive increase in their popularity, leading to what is generally termed the ‘Golden Age’ of postcards. An example of the scale of postcard enterprises may be found with the London-based stationery and printing firm of Raphael Tuck & Sons Ltd. From printing their first series of Pictorial Postcards in 1899 of London views, they had 10,000 different cards by 1903 (Staff, 1966; see also Anon, 2017). The popularity of postcards meant that a massive range of images were produced, from the unique to the mundane. Museums and ancient monuments – the subject of the burgeoning wave of tourism - were prime subjects for postcards. It is difficult to pinpoint the first time a British museum is depicted in a postcard. Staff (1966: 65) has suggested the earliest instances were in postcards manufactured by the firm of Wrench in the early 1900s for (privately owned) Warwick Castle, some Office of Works sites, the National Gallery and the Tower of London. However, Sadler’s recently published collection (2016) demonstrates the range of museum postcards at this time was much broader, featuring postmarked postcards depicting the following: British Museum (1901), Grand Hotel, Museum & Aquarium, Scarborough (1902), Bury Art Gallery (1903), Harris Free Library and Museum, Preston (1903) and Leicester Museum (1903). Significantly, the British Museum card was manufactured by Raphael Tuck while the Scarborough card was produced in Saxony, reflecting the continental nature of the postcard craze. The extent to which museums benefited economically from the early circulation of these images is unclear. Staff (1966: 65) does not comment on whether commercial agreements were in place in order for these cards to be sold onsite. It does seem likely that for internal photography of museums some negotiation (and therefore consent) was likely entered into, but the situation is unclear where only the exterior of museum building was the subject, particularly for sites that did not sell postcards themselves. One of the earliest recorded examples of a museum pro-actively harnessing the popularity of postcards is the British Museum. In 1912 the Museum partnered with Oxford University Press and produced a range of postcards detailing items in its collection, ranging over 135 subjects and costing one penny each. The same year the Museum introduced its first catalogue stall, providing, for the first time, a bespoke sales area for its publications, guidebooks, and its range of postcards. This was a specific effort to attempt to ‘widen the influence and increase the interest of the museum’ (British Museum, 1913).The Museum sold 155,000 postcards in its first year, and the endeavour was judged a great success in subsequent annual reports. In this context postcards provided popular, educational souvenirs for visitors that allowed the Museum to disseminate particular images of its collection. It also provided a useful economic resource for the museum that would play an important part in funding the organisation’s publications schedule in years ahead (see Larkin 2016: 68-96). While similar schemes were introduced at institutions of comparable size, such as the National Gallery (1915) and the V&A (c.1915), development in the provinces was probably somewhat slower, as it was unlikely that either appropriate sales infrastructure or a desire to enter into commercial relationships were in place. An indication as to how these relationships played out may be gleamed from the Dorman Museum, Middlesbrough. In 1914, Baker Hudson, the librarian and curator received a request from a Mr Beckwith, a photographer, who proposed to take photographs in the gallery for reproduction as postcards. He suggested a small fee in lieu of royalties, but this was something the rate-funded Library and Museum did not feel they could accept and the offer was declined. The earliest reference to the Museum selling postcards is 1926 (Louise Harrison, pers comm, 2015). Beyond commercial considerations, which for all but the larger sites would have likely been nugatory, the more important aspect of postcard production was that institutions were able to control visual representations of their site and collections. This was the case for ancient monuments, which in the early years of the 20th century had become increasingly popular with day-trippers. With this growing tourism souvenir sales had taken hold at a number of sites, in particular Stonehenge, resulting in variety of images of the site in circulation (see Richards, 2009). When Stonehenge was taken into guardianship in 1918, the Ministry of Works prohibited such paraphernalia, introducing their own guidebook and postcard selection shortly afterwards, enabling them to frame interpretation of the site in ways they saw fit. By the 1930s, the growth of postcard sales at museums and other site had become more commonplace. Indeed, new series were announced in the Museums Journal, such as a series of 12 that Peterborough Museum published in 1934 (vol 34/iss 2). Intriguingly, the influence of postcards on taste was specifically addressed by J.E. Barton (1934: 309), in a speech to the Museums Association in the 1930s. He noted:

"All of you are forced by circumstance to retain on your walls many pictures that you know are bad, pictures that you would burn if you could. Might you not at least refrain from trading in postcards which perpetuate these empty survivals, and the sale of which appears to invest them with official commendation. If you take a parallel from literature, no State-aided school would now be permitted to bring up its pupils on the poetical works of Mrs. Hemas or Adelaide Anne Procter. But the postcard and photograph stalls of every museum in the country give actual prominence to pictorial works, compared with which the lyrics of those ladies are intellectually important and emotionally dignified." Here then, postcard was deemed so important to the overall cultural impact of museums, that a curatorial focus on the commercial aspects of the institution was called for. Such calls were increasingly made into the 1940s and 1950s, with a report drawn up for Dartington Hall noting that the purpose of art galleries should be ‘to stimulate a wider and deeper knowledge and appreciation of art and design in order to raise the prevailing standard of public taste’, and that postcards have an important part to play in such endeavours (DHT, 1946: 31, 105). Conclusion Further work needs to be done to develop a more detailed understanding of the cultural and economic impact of museum postcards in the museum, but it is clear that their introduction played, and continues to play, a small but significant role in museum operations. Postcards provide a means by which museums can regulate external images of cultural objects beyond the galleries, what Malraux (1967) has termed the ‘museum without walls’. Moreover, the sale of these items created a commercial aperture in the museum: a space in which visitors could make choices on the types of image to take away with them, creating a feedback loop that would gradually inform relations between the museum and its public. Hopefully this post shows that areas of museum activity that are often considered incidental to its core curatorial function can reveal important insights. Indeed, there are a number of other areas ripe for exploration, looking at historical museum operations from the broom cupboard, to catering facilities, to the board room. Specifically, approaching museums in this way serves to reintroduce the human aspect to their study. As much understanding the historical outputs of these institutions, we need to understand how museums were used as living, working, spaces. Perhaps nowhere has the social aspect been better broached that in Penelope Fitzgerald’s (2014 [1977]) fictionalised account of the British Museum in The Golden Child. In the end, through knowing more about the inner workings of the institution, we may better understand the ways and means by which public culture has been and continues to be produced. References/Further Reading Published sources Anon. 2017. History of Raphael Tuck & Sons Ltd. [accessed 15 July 2017]. Available at: https://tuckdb.org/history Barton, J.E. 1934. The Education of Public Taste. Museums Journal 34 (8): 297 -308. Fitzgerald, P. 2014 [1977]. The Golden Child. London: Fourth Estate. Larkin, J. 2016. 'All Museums Will Become Department Stores’: The Development and Implications of Retailing at Museums and Heritage Sites. Archaeology International 19: 109–121. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ai.1917 [open access] Larkin, J. 2016. Trading on the Past: an examination of the cultural and economic roles of shops at museums and heritage sites. Unpublished PhD thesis, University College London. Malraux, A. 1967. Museum without walls. New York: Doubleday & Company. Richards, J. 2009. Inspired by Stonehenge. Stroud: Hobnob Press. Sadler, N. 2016. Museums: The Postcard Collection. Stroud: Amberley. Staff, F. 1966. The Picture Postcard & Its Origins. London: Lutterworth Press. Unpublished sources British Museum. 1913. Account of the Income and Expenditure of the British Museum for the year ending the 31st day of March, 1913. London: British Museum archive. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed