|

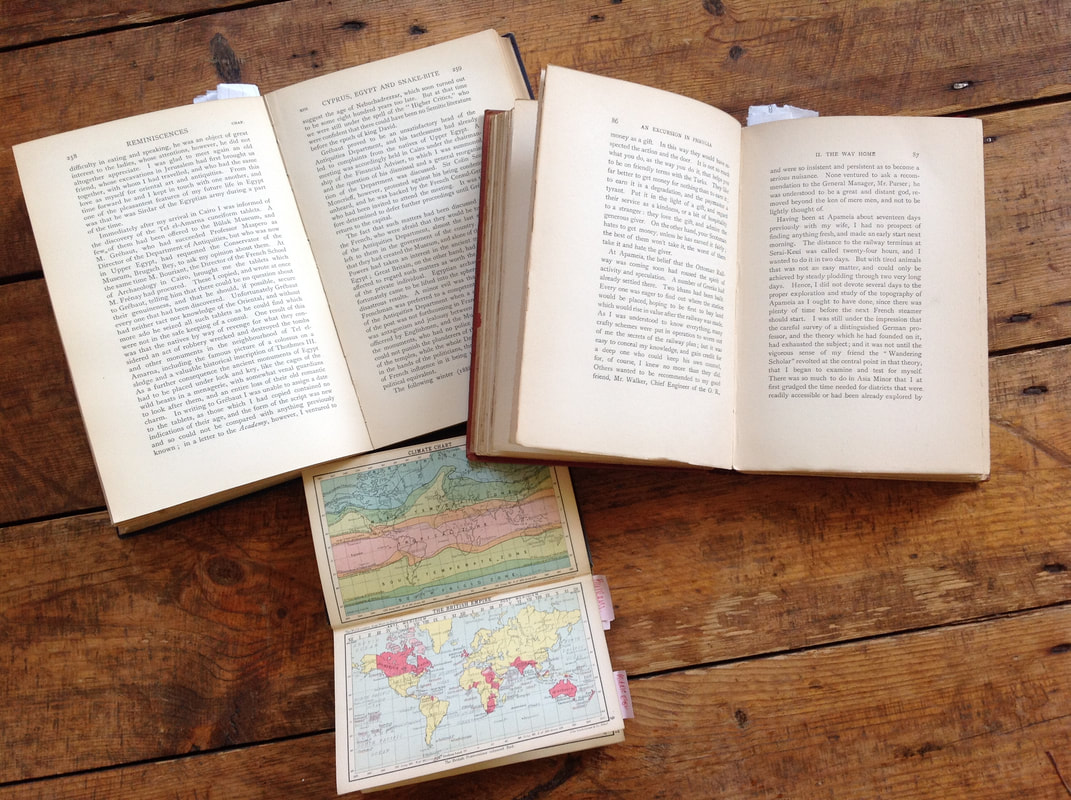

Thomas is Curator of the Cyprus Collection at the British Museum. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? TK: In a basic way, it is – or at least should be – just a subsection of the histories of science/exploration/discovery, broadly defined, as well as I suppose of the disciplinary developments within archaeology itself. Tim Murray and others have noted how archaeology has tended to define its own history pretty much from the beginning of its institutional phase in the later 19th century, and has generally been written by archaeologists, so it has generally avoided the same scrutiny as the history of science which has a much broader disciplinary base. At the same time, it’s also a subsection of general imperial and colonial history, especially when carried out in areas that came under imperial and colonial control, and where diggers had explicit agenda – though saying that, the broader urge to explore and record can be found in among naturalists or ethnographers who often were interested in antiquities. More broadly still, it’s the history of ‘encounters’, including within countries where elite collectors and excavators (often local landowners and bigwigs) mapped out nations and controlled their histories through their recording of archaeological remains. One shouldn’t put as much emphasis on the social and political impact or aims/ideology of archaeology as is widespread nowadays, but I think you can represent the history of the subject as a search for origins and identities, but also of change and flux, regardless of where or how this actually happened. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? TK: Mainly 18th to 20th century Cyprus (and the Eastern Mediterranean in the same period more broadly), though working in a British Museum (BM) Mediterranean environment inevitably pans out into broader fields, such as museum procedures and admin – sounds dull, but is interesting (and certainly necessary) as we are very concerned about how we report and reflect our collecting history. I'm also fascinated by the role of the antiquities market in defining museum acquisitions and valorisation of artefacts. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? TK: Like lots of people interested in archaeology, I was fascinated by the history of discoveries, which is probably how a lot of us get into the subject. Ironically, that interest probably waned as I started to study archaeology at university. I remember the lecturer in my first year core archaeology class talking about antiquarians and old archaeological theories, but even if he didn’t like Processual archaeology, he tended to be relatively dismissive of earlier archaeologists. When I was doing my PhD, I saw the history of the subject as a sideshow, and like many just rolled my eyes at what I saw as the ridiculousness of early excavators, such as Luigi Palma di Cesnola. I certainly didn’t realise how important archives were for archaeological purposes, let alone broader historical questions. It was only when I started work at the BM, and began to engage with the subject from within the archive, that I got hooked – first because I realised that you couldn’t understand the collections archaeologically without knowing how they were found and handled, and then more historically in understanding the motivations of early archaeologists. Bit by bit, all the different bits of the subject coalesced into what I hope is a more joined-up interest in the subject. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? TK: I’m finishing a big edition of correspondence relating to various phases of the history of Cypriot archaeology in the 19th century, from the late Ottoman consular activities to the fairly large-scale expeditions of the British Museum. Related to this, I’m also co-working on a paper on a Cypriot antiquarian and collector, Demetrios Pierides, and his relationship to the antiquity market – something that really interests me, as it’s very relevant to modern discussions of the trade. Finally, I’m also involved in a series of workshops on archaeology in the British colonial period in Cyprus with Lindy Crewe, Director of the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute in Nicosia and Anna Reeve, University of Leeds. It had to go virtual, but the benefit is now that you can all join in (www.caari.org/programs). AT: What, from your experience, is the most exciting thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? I think it’s fair to say that as in archaeology itself it’s often more a question of many small discoveries, and eureka moments when things start to connect in a way they didn’t at the beginning. Likewise with finding documents and photographs that you thought were missing, but were simply in a different file. Finding original photographs is always exciting, especially when they show local people – the elephant in the room of the history of archaeology. The edition of correspondence I mention above is joining up lots of individual stories and making sense of things which were very vague at the beginning. One very fun discovery was the Latin-based telegraphic code used by the British Museum’s supervisors in Cyprus to communicate with London. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. TK: I have to be loyal to the books that first inspired me. Henri-Paul Eydoux’s In search of lost worlds (whose original French title, A la recherche des mondes perdus is clearly a play on another far less interesting book!) and Michael Wood’s In search of the Trojan War – I bought this book after seeing the memorable TV show back in the day when a TV company would make a 6 part documentary on one subject! Of more recent titles, I really like Maya Jasanoff’s Edge of Empire, Zeynap Çelik’s About antiquities on Ottoman archaeology, while Jacqueline Yallop’s Magpies, squirrels and thieves is a great read on collecting more generally. Likewise, Karolyn Schindler’s biography of Dorothea Bate, Discovering Dorothea, is great – Bate was primarily a palaeontologist, but her contacts and networks all overlapped with archaeologists and their broader worlds. They all in a sense project a sense of the serendipity and subjectivity, of how much individuals shaped the disciplines (and often went against the social grain). They all have great narratives, which are essential to the subject itself, but especially in engaging broad audiences. I love reading old travel accounts too, even if you have to take a deep breath at the prejudices expressed. One great joy of working where I do is our stunning collection of early books of travel and exploration, especially archaeology, and it’s wonderful to look at them in their glorious original scale and smell. My department has two (!) sets of Richard Pococke’s Description of the East of 1751. It’s a marvel. Conversely, while I won’t name names, but there are also loads of rather mundane chronicles of archaeological discovery out there that leave a lot to be desired. And, lots of writing on the subject is frankly a bit dull, especially when aspiring to being hyper-intellectual. It kind of squeezes the joy out of the subject and leaves potential readers of critical history rather cold. AT: Is there a key object/image/text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? TK: I really love the surviving field notebooks where excavators recorded their finds and began to grapple with what we would now call the ‘discipline of archaeology’. There is one by John Myres where he records the finds from tombs at Amathus in Cyprus a really meticulous way, but at the back are loads of scribbles and thoughts but also an attempt to ‘seriate’ the tombs in order to date them better. Myres has been called the ‘father of Cypriot archaeology’, and you can see his mind working, and the discipline coming into being in front of your eyes. I also love photographs, and one I have in mind shows a large marble capital from Salamis in Cyprus being dragged through the streets of Famagusta in 1891. It shows Royal Navy personnel and lots of local workers, but also the on-looking provide a kaleidoscope of the diverse late Ottoman/early British local community. Oh to have been there…

AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? TK: Reads lots of older archaeological accounts and narratives of discoveries, rather than the many tedious commentaries on them that sometimes pass as historical analysis! You have to read the latter too, but try not to put Descartes before the horse… I think a solid grounding in the history of the region you are interested in is also essential. Things start making sense in an organic way, and you start to realise that archaeology was – in my view – not as important or ideological as is often said in narrow histories of the subject. This would also I think address some of the problems with the lack of knowledge of imperial history that is a big problem today (see next question). Also, develop an interest in biography, micro-history (and related empathetic approaches), and general narrative, but also in the materiality of archival documents – and I think working with archival documents is essential and exciting. Finding an archival niche is I think one of the things that open up the subject and connects with public audiences. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? TK: Well we are all post-colonial now, and there are a lot of discussions mediated through various post-colonial lenses that we have to address, especially the contextualised collection histories of museums and better understanding imperial history. How effective and convincing these discussions are remains moot because I think we tend to jump from very general post-colonial perspectives to very specific archaeological ones without a huge amount of nuance – hence my suggestion that we need to have a very solid grounding in general history. I think we certainly need to address under-representations of archaeological agency – especially gender (cherchez les femmes!) and local communities (from digger and foremen to local elites who collected and studied antiquities – and often collaborated with the acknowledged archaeologists). I think that is one of the key post-colonial insights we can advance with very little effort, just as social historians transformed how we saw history ‘at home’ in past decades. Global knowledge justice is certainly our remit too – the recent lockdown simply reinforced the problem of access to archives (and collections). I think if we could open up our archives in a digital way that would address some of the problems. Saying that, I think we also need to expand the public awareness of archaeological and museum histories far beyond present conceptions. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? TK: Despite what I said about the importance of digital, I don’t tweet or blog! You might find random visual musings on Instagram which I like to imagine as archaeological Wombling (nebulatrope). Maddy Pelling is an art historian specialising in the history of archaeology and collecting in the 18th and early 19th centuries. She is currently working on a postdoctoral project on the history of women antiquarians in the UK during this period. We discuss the evidence for women excavating, researching and publicising the material culture of the past, and the importance of local contexts, identity and colonialism in the history of archaeology. Listen to our conversation here. Follow Maddy on twitter @maddypelling.

Read Maddy's comments on the excavations at Warminster in the online edition of Vestuta Monumenta. Listen to Maddy's paper, "Digging Up the Past: Contested Territories and Women Archaeologists in 1780s Britain and Ireland" at the Open Digital Seminar in 18th Century Studies. Further Reading/References Lake, Crystal. 2020. Artifacts: How We Think and Write About Found Objects. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Raiders of the Lost Past with Janina Ramirez: The Sutton Hoo Hoard (BBC4) Dr Gabriel Moshenska is a Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? GM: I think there’s different ways of approaching this question. There’s no single history of archaeology, just as there is no one best approach to its study. I’m particularly fascinated by biographical approaches – individual, group, and object-focused biographies. History of archaeology can rise up from the grassroots – sites, artefacts, archives, balance sheets, individuals, institutions – or it can descend from the clouds of theory, and trace concepts and models onto the crooked timber of archaeological humanity. I like the diversity of it, even if I’m rather unimpressed with quite a lot of the work that takes place within that diversity. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? GM: Primarily, I’m engaged in a biographical study of Thomas Pettigrew, the surgeon-antiquarian who became well known for holding public unrollings of Egyptian mummies. I’m assembling his intellectual biography in fragments, and currently looking at his work as librarian to the Duke of Sussex, and the liberal political milieus that this brought him into contact with. I have other strands of interest as well – perhaps too many – including the history of archaeology in London, from Charles Roach Smith through to the present. Through my Pettigrew work I’ve become very interested in the early history of the British Archaeological Association, and the rise of archaeology as a bourgeois pastime in the mid-nineteenth century. Most recently I did some work looking at the history of protest movements at archaeological excavations, and the nature of public ‘save the heritage’ campaigns, that often come to regard archaeologists as their enemies. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology?

GM: During my PhD I became very interested in the epistemological significance of eye-witnessing in archaeology, and the role of expert and amateur audiences at excavations. This led me into historical studies of public archaeology, including Pettigrew’s mummy unrollings. Then I started working on archived correspondence of archaeologists and antiquarians, and there was no going back. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? A long-overdue book! I’m also wrangling with the late Peter Gathercole’s research notes on Gordon Childe, which contain a wealth of fascinating material. Related to this, lately I’ve been enjoying Katie Meheux’s penetrating and illuminating work on Childe. AT: What, from your experience, is the most exciting thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? Correspondence between two antiquarians – Robert Lemon and Thomas Pettigrew – from 1826. Lemon reported to Pettigrew that he’d discovered a long-lost theological work by John Milton in the State Paper Office. Knowing sod-all about Milton, and having no wifi in the British Library manuscript room at that point, my first thought was blimey, what a discovery! Does anybody know about this? Fortunately the existence of De Doctrina Christiana is well known, but I was able to add a few details to the history of its rediscovery and attempts to variously authenticate and debunk it, and publish a short paper in Milton Quarterly. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? GM: I very much enjoyed From Genesis to Prehistory, Peter Rowley-Conwy’s book on the contested reception of the three age system, it struck a lovely balance between the big ideas and the people behind them, and it was very well written. Philippa Levine’s The Amateur and the Professional is a book I return to again and again in my work, with ever growing appreciation for its breadth of understanding of Victorian antiquarianism. In terms of fascinating subject matter and superlative prose, The Master Plan, Heather Pringle’s study of Nazi archaeology, is unmatched. I highly recommend it to all archaeologists, particularly those naïve fantasists who cling to the idea of an ideology-free science of archaeology. AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? GM: One of the strangest episodes in Thomas Pettigrew’s career was his mummification of the tenth Duke of Hamilton in 1852. Pettigrew carried out the embalming in the traditional Ancient Egyptian manner, and conducted a full faux-Egyptian funeral service, after which the Duke’s remains were interred in a genuine Egyptian sarcophagus. I read a letter from the Duke’s valet to Pettigrew in the Beinecke Library that said (I’m paraphrasing obviously) ‘The Duke just died, please come and bring the embalming spices’. I was and remain fascinated by the disparity between the outlandish strangeness of the event, and the banal matter-of-factness of the letter that heralded it. Thinking about this helps me keep the sense of wonder in my research, and a reminder not to feel too familiar or comfortable with the people and events that I’m studying. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? GM: There is so much still to do, so much incredible material lying untouched in archives. Don’t stick too closely to what’s been done before – blaze a new train through the sources and the ideas. And for god’s sake, read deeply in the historiography of science so you don’t make a fool of yourself. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? GM: The poverty of historiography. The huge amount of published research which is sub-antiquarian dross, boot-licking hagiography, or unoriginal piffles-about in stale secondary sources. We often talk about archaeology as a tool of European imperialism, but I think there’s a great deal more to be done looking at the details and operations of this mechanism. For example, I would love to know more about the roles of British archaeologists in colonial expeditions, invasions, and punitive raids. __ Follow Gabe on twitter at @GabeMoshenska or email him and ask for pdfs. Dr Nicole Cochrane is a historian of archaeology specialising in the history of collecting in British museums in the 18th and 19th centuries. We discuss Nicole's route into research in the history of archaeology, her work on the Townley Gallery at the British Museum, and some inspirational objects and texts from her experiences. Listen to our conversation here. Find Nicole on Twitter @tinyhistorian. Further Reading

Bignamini, I. and Hornsby, C. 2010. Digging and Dealing in Eighteenth-Century Rome. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. Carruthers, W. (ed) 2014. Histories of Egyptology: Interdisciplinary Measures. London: Routledge. Procter, A. 2020. The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums and Why We Need To Talk About It. London: Cassell. Riggs, C. 2018. Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt and the Archive. London: Routledge. As a response to the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic, the History of Archaeology Network will not be running seminars this year. Instead, we will be taking a different born-digital approach, showcasing the latest history of archaeology research and examining current trends in the field. This post introduces our new "Historians of Archaeology" series. We'll be interviewing historians of archaeology throughout the year. We'll discuss their research, what makes them excited about this research, and, critically, how the history of archaeology speaks to current issues and events.

Inspiration for the series comes from the Killing Time podcast, The Wonder House podcast and the Museum of British Colonialism's Paper Trails blog. |

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed