|

Dr William Carruthers recently finished a Leverhulme Trust funded project at the University of East Anglia, where he is an Honorary Lecturer in the School of Art, Media and American Studies. Among other things, Will and I discuss sources, decolonisation, and most of all his new book, Flooded Pasts: UNESCO, Nubia and the Recolonisation of Archaeology (Cornell University Press, 2022). Listen to our conversation here. Link to Will's book, Flooded Pasts https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9781501766442/flooded-pasts/#bookTabs=1

Other books mentioned: Lucia Allais: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/D/bo28907758.html Ann Laura Stoler: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691146362/along-the-archival-grain Menna Agha: https://architecture.carleton.ca/archives/people/menna-agha Subha is is a final year PhD candidate at King's College London. In a slight departure from the usual questions in this series, this interview highlights the role of biography in the history of archaeology, through the case study of late 19th/early 20th century British archaeologist Nina Frances Layard. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: Tell us a bit about Nina Layard.

SRW: Nina Frances Layard was born in 1853 in Essex. Her interests in archaeology was publicised when she moved to Ipswich in 1889. Here, Layard was responsible for unearthing instrumental archaeological discoveries that would gain her reputation as one of the leading archaeologists during her time. Layard’s discoveries at Foxhall Road between 1902-1905 where she unearthed a Palaeolithic brickearth is one of her most cited legacies in discourses about her archaeological career. Though, Layard’s excavations expanded beyond provincial spaces and gained her recognition in prestigious scientific institutions. Her excavations of an Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Hadleigh Road in 1906 led to her Fellowship at the Anthropological Institute and later the Linnean Society (1906). In 1921, Layard was one of the first elected woman Fellows at the Society of Antiquaries. She was also Editor of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology& Natural History journal. As a devout Evangelical Anglican, Layard’s theological beliefs were never separated from her scientific thinking. Her interest in Evolutionary Theory in 1890 led to a wave of debates and a newfound audience due to her challenging of Darwin’s theory of ‘Reversions.’ Here, we see the intellectual rigour of Layard’s ideas in reckoning with the authority of religion in the scientific debates during her time. Layard presented these ideas by speaking at a range of institutions across the country including the British Association and the Victoria Institute. She was also a regular scientific writer for the Science-Gossip Magazine and was an acquaintance with the editor at the time Dr John Ellor Taylor. Apart from her scientific and archaeological interests, Layard had a unique poetic identity. Citing influences like Robert Browning, Layard adopted complex poetic verses to draw links between her scientific and religious ideologies. As a woman navigating her role as an archaeologist and scientist within institutions which were dominated by men, Layard confronted the discriminations she faced by affirming her authority and presence within masculinised, heteronormative scientific spaces. Although Layard’s relationship with Mary Frances Outram was not publicised during her time, the portrayal of their relationship and the expressions of their desire is important to integrate in writing about Nina Layard. For full biographical details see Steven Plunkett: Miss Layard Excavated: a Palaeolithic site at Foxhall Road, Ipswich, 1903-1905 (2004) AT: What drew you to researching Nina Layard? SRW: I first encountered Nina Layard’s work during my MA when I was researching the receptions of Austen Henry Layard in the popular press for my MA dissertation. A large part of Austen Henry Layard’s archival records are held at the National Library in Scotland and it was through looking at letters and correspondences there that I learnt about Nina Layard’s archaeological contributions in Ipswich. I came across an interview with Dr Sarah Irving and she describes how she encounters the most exciting finds by accident and I really resonate with this in reflecting about how I came to research Nina Layard. In the early stages of my research of Nina Layard I looked first at how she was represented in the press. There still isn’t much secondary criticism or engagement with Layard’s work so a lot about her work and life is contained within her archival material and press reports of her. I noticed how common it was to find newspapers describing Nina Layard as the niece of Austen Henry Layard as a way of establishing her relevance. By the late-nineteenth century, Austen Henry Layard was known nationally for his excavations at Nineveh but Nina Layard’s work wasn’t popularised on the same scale so newspaper editors introduced her by her association to Austen Henry Layard. From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, the national press and indeed provincial papers were captured by archaeological excavations and expeditions at sites in the Near East and Egypt. In response, this profile of the archaeologist as the heroic, authoritative figure, problematically linked to the imperial legacies of these excavations were featured more prominently in the press and in turn, archaeological work that didn’t engage with these excavations were not represented on the same scale and therefore remained less accessible. What interests me about Layard is that the press is how Layard self-fashions her identity as an archaeologist - through her relationship with the printing press. From 1898 onwards, she begin writing a regular column for the East Anglian Daily Times and in these columns, Layard wrote about the excavations she led and sometimes published historical insights of Ipswich. In taking up this space in the press, Layard’s writing is in itself a kind of resistance to the colonial, imperial narratives that were publicised in this period. My research begins by looking at the relationship between Layard and the provincial press and how she shapes her legacy through this space. AT: What in your opinion makes Nina Layard a significant figure? SRW: Nina Layard’s contributions to areas of prehistoric archaeology, Evolutionary Theory, botany and literature suggests the breadth of Layard’s intellectual pursuits. While she was by no means the first woman to hold multiple interests, Layard pursued her academic interests independently and was persistent in her commitments to articulating and publicising her ideas alongside well-known scientists during her time. Her multifaceted and often intertwining interests makes her work complicated to synthesize independently; instead it’s important to recognise how her literary, activist and religious ideologies are interwoven in her archaeological thinking. One of the areas where this is particularly prominent is in her poetry where Layard’s Evangelical Anglican background informs the ways in which she reads and reconciles with the past. While Layard cites poets like Robert Browning whose poetic style is echoed in the construction of her poetic verses, situating Layard’s thinking and writing amongst her contemporaries highlights her unique way of drawing together a multiple ideas and concepts to reassess the past calls to an interdisciplinary approach to deconstructing her work. AT: How have you integrated Layard's literary and archaeological work in writing up your research? SRW: Although Layard’s poetry has not gained sustained engagement in recent scholarship, her poems received critical acclaim and public recognition during her time. Encouraged by the critic and poet Andrew Lang, Layard’s poems were published in prestigious platforms such as Longman’s and Harper’s magazine. Like the rest of her oeuvre, Layard’s poetry is not defined by a single theme, instead her poetic verses are reflective of the rich depth of her curiosities: ranging from archaeological reckonings to other scientific dwellings including her interest in botany and natural selection as well as her preoccupations with issues concerning religion and romantic desire. Taking into consideration the broad themes that are imbued in her poetry, my second chapter places Layard’s scientific thinking within the context of the relationship between literature and science. Here, I’m thinking more specifically of Michael Shanks’s theory of the archaeological imagination and how Layard’s poems which explore archaeological and antiquarian themes rely on the literary verse to access narratives of the past. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in researching Nina Layard? SRW: Spending a large part of this PhD in Nina Layard’s archives which is located at the Hold in Ipswich has been tremendously rewarding. Her archival material - from her unpublished writings, photographs, letters of correspondence with leading scientists and curators of the time shows us Layard’s scientific and creative authority she held in all stages of her career from her excavation work to the curatorial representations of her work. Alongside my research on Nina Layard, I have particularly enjoyed researching and writing about Layard’s partner, Mary Frances Outram who was hugely integral to Layard’s professional success. In regards to Layard’s archaeological pursuits alone, Outram frequently accompanied Layard to excavation sites and utilised her painting and watercolour skills to provide illustrations for Layard’s archaeological sketches. In incorporating a queer reading here, I am interested in how the expression of their queerness in the archaeological site instigates expansive and non-normative ways of thinking about archaeological practices and how this was presented to the public. AT: In your opinion, what is Layard's legacy and in what ways would you present Layard's life and legacy to the public? SRW: Layard’s legacy is quite multifaceted. Her contributions to archaeology, poetry and evolutionary theory were challenged traditional beliefs during her time. I think it would be useful to interrogate her rich archival resources and exhibit them in some way. These materials not only give an insight into Layard’s work but also demonstrates the communities she helped and worked with, the political debates she was engaged in and the social issues she cared about. Additionally, I think a biopic on Layard’s life will also be quite extraordinary! AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) that you've found particularly useful for your research on Layard? SRW: Amara Thornton’s Archaeologies in Print (2018) is a crucial book in thinking about how influential publishing was for publicising and accessing women’s archaeological writing. Clare Stainthorp’s Constance Naden; Scientist, Philosopher, Poet (2019) offers a critical and comprehensive approach to researching an individual who was overlooked in the Victorian period. Stainthorp’s theoretical underpinnings offer critical insights into how to structure research on a single individual and their multiple legacies. Andrew Hobbs’s article on ‘How local newspapers came to dominate Victorian poetry publishing’ (2014) has been really useful in thinking about how the provincial press was instrumental to shaping local readerships and literary communities in local towns. Alice Procter’s The Whole Picture: The colonial story of the art in our museums (2020) is also a really important and crucial book to read. AT: Do you have any advice for researchers embarking on research about an individual related to archaeology? SRW: Researching Layard’s work demonstrates really clearly that an individual’s contributions to archaeology can be wholly understood if we take into consideration the communities they were part of, who they were in conversation with and how these influences impacted their thinking. To access this information, engaging with archival work and historical records of the individual’s relationship with these networks and institutions allows us to contextualise their contributions to archaeology more truthfully. Looking into the reception of an individual’s archaeological work also highlights how their discourse travelled and how forms of this archaeological knowledge were reconstructed based on the spaces they occupied. One way of looking into this is whether the individual engaged with spaces beyond the metropolitan, where perhaps access to scientific and archaeological institutions were less prominent. Also important to explore how non-scientific networks were equally as important to formalising an individual's archaeological works AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues to reflect on in how we research and write about individual women who were notable in the past? SRW: In regards to Layard, I found it useful to start by looking for current discourse about her work and how/if scholars were writing about Layard and in what context. It's useful to look into the gaps of knowledge that exist and to interrogate why specific histories are omitted from current discourses. This of course then brings us to thinking about the shifts in the political and cultural context over time and how scholars have reconsidered the representation of women in the past. In this regard, a historiographical and biographical approach offers a more nuanced approach into how women navigated archaeological institutions and spaces that were not always accessible to women. I think it's also helpful to look at how women were represented beyond scholarly contexts and how other forms of media are more transparent about women’s lives and contributions to the discipline. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? SRW: I am currently writing about Nina Layard’s articles in the East Anglian Daily Times for the Journal of Victorian Culture which I am hoping will be out later this year. Sarah is Lecturer in modern Middle Eastern history at Staffordshire University. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? SI: I’m not sure I’m properly a historian of archaeology – I’m more of an interloper who uses historical records of archaeology to look at social and gender history – so I’m not sure it’s entirely my place to define it. But from my perspective it’s the history of how archaeological and the search for material remains of human activity is carried out, not just by professionals in the field but also in terms of its relationships with the people surrounding it – labourers, farmers on archaeological land, guards and museum attendants, people who read about and watch films of archaeology, interact with it in exhibitions and in discussions… and so on. AT What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? SI: I primarily look at the role of ordinary Palestinians and other people from the Levant region in the conduct of archaeology in Late Ottoman and Mandate Palestine. This ranges from educated Christian Lebanese who worked at supervisors on excavations for the Palestine Excavation Fund for many years and who became quite significant figures in how the archaeology of their period was enacted and interpreted, to women and men from nearby villages who were manual labourers on excavations, perhaps only for a total of a few months, or to some of the (usually but not always) nameless guards and other workers who were employed by the Department of Antiquities of the British Mandate administration in Palestine, or the lower-level dealers and go-between from the Palestinian Syriac Orthodox community who were the conduit by which various museums acquired the Dead Sea Scrolls. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? SI: In a parallel universe I went to university nearly 30 years ago and stuck with the archaeology I started then. In actual fact the course at Cambridge bored me so badly that I switched to anthropology – I should have stood up to my school better and gone to Sheffield, but who makes good decisions at 18? I went back to university to do a PhD in my late 30s and became a social historian of Palestine, but by various roundabout routes (involving looking for something completely different in the archives of the PEF) I’ve ended up combining the two in a lot of my work. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? SI: Although my main research project at the moment isn’t history of archaeology – it’s on the 1927 earthquake in Palestine, so it does still have overlaps with the material environment and how that affects history – I am working on a couple of papers in HoA. One is for a conference next spring run by Michael Press at Agder University, for which I’ll be looking at the sale of antiquities, including Dead Sea Scrolls jars, by the Department of Antiquities/Palestine Archaeological Museum in the Mandate and Jordanian periods. I also have an article coming out in Jerusalem Quarterly taking a long-view look at the lives and working conditions of guards on archaeological sites in the Mandate period, especially at Athlit and Jericho, and how those intersect with the broader political situation in the country, and I’ll be speaking on the same broad subject at a Bade Museum/PEF online talk later this month. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? SI: The archives from the pre-WWI Harvard University excavations at Sebastia, which are at the Harvard Semitic Museum, include the fortnightly pay lists, which means they have long lists of the names of every worker on the site, men and women, how many days they worked during that period, and how much they were paid. Given how little we know about the lives of ordinary Palestinians over a century ago, how much information has been lost in the wars since, and how many Palestinians have been displaced as refugees, to able to get that snapshot of what such a large group of people were doing is amazing. Archaeological records aren’t often on the radar of social historians but sometimes they can be amazingly rich sources. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. SI: Given my subject area, the main ones would be other explorations of workers on archaeological sites, so Stephen Quirke’s Hidden Hands: Egyptian Workforces in Petrie Excavation Archives, 1880–1924, parts of Elliott Colla’s Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity and Donald Malcolm Reid’s books Contested Antiquities in Egypt: Archaeologies, Museums and the Struggle for Identities from WWI to Nasser and Whose Pharaohs? Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to WWI, and of course Amara Thornton’s investigations of archaeology in Palestine during the Mandate period. Going beyond books, I’d also like to flag up Unsilencing the Archives[https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/9eb391c6f57f4399a58ecf9b818e6762], an online exhibition curated by Melissa Cradic and Samuel Pfister, which is an amazing look at the workers at Tel en-Nasbeh during the Mandate period and which includes video footage from the late 1920s of archaeological labourers at work. AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? SI: There is a photograph in the PEF archives of two Palestinian women at the Tel Jezar site, I think during R.A.S. Macalister’s excavations there, sieving for small finds. One of them is looking straight into the camera. She’s mid-work, sitting on the earth, staring at us with a really no-bullshit look on her face. She’s just as much part of the history of archaeology as a guy in a pith helmet and puttees whose name is on all the publications about Gezer, and I want to know as much as I can about her life. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology?

SI: The best information is never where you expect to find it. To amend a well-known saying, the best way to make the Gods laugh is to tell them your (research) plans – my most exciting finds have always been accidents, usually when I’m looking for something completely different. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? SI: I would say that getting away from the Indiana Jones/dead white men view of archaeology is one of the biggest things – especially decolonisation, but also finding the female, black, Muslim, gay, Arab, Asian, indigenous, non-literate, working-class etc etc people who contributed to archaeology but whose names aren’t in the published records. And moving on from that, communicating this so that the public view of archaeology (and perhaps even more the view of TV producers) evolves away from treasure and ‘exploration’ to some more nuanced understandings of who does/did archaeology, why, and what its impacts were for their lives and communities. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? SI: I rant a lot on twitter at @DrTermagant, and am less ranty on my project twitter handle at @JerichoQuake27. Otherwise, my profile page on the Staffordshire University website (when that goes up) should list publications and have access to those which are open access, and have information on my current research. Debbie is Education and Outreach Officer at the London School of Economics Library. She and I discussed many things including racism in the history of archaeology, emotions in the history of archaeology, making connections to wider histories and contexts, and the importance of good metadata in archives. Listen to our conversation here. You can find Debbie's two posts on Hilda Petrie and suffrage, written for this website here. Debbie's work published open access:

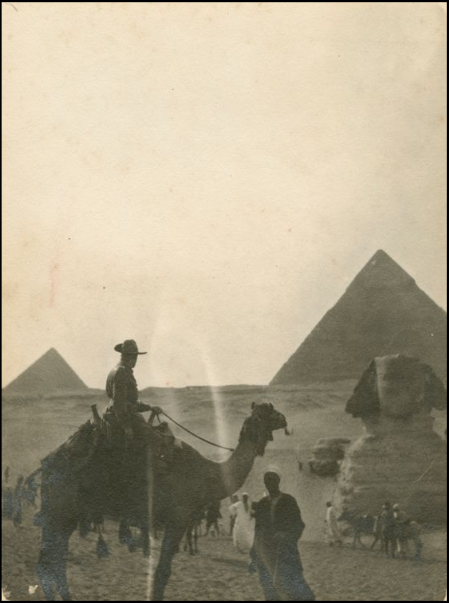

Challis, D., 2016. Skull Triangles: Flinders Petrie, Race Theory and Biometrics. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 26(1), p.Art. 5. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/bha-556 Open Access Challis, Debbie and Romain, Gemma (2015), A Fusion of Worlds. A / AS Level Learning Resource on the Equiano Centre Website, (Department of Geography UCL): https://www.ucl.ac.uk/equiano-centre/educational-resources/fusion-worlds/context/ancient-egypt-culture-and-barbarism [accessed 13 July 2020]. 2021: ‘Back to Back: Babies, Bodies, Boxes’ in Carruthers, W. 2021. Special Issue: Inequality and Race in the Histories of Archaeology. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, X(X): X, pp. 1–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bha-660 With Daniel Payne, ‘Giving Peace a Chance: Archives engagement at LSE Library’, Andrew H. W. Smith (ed.), Paper Trails. The social life of archives and collections, UCL Press: https://ucldigitalpress.co.uk/BOOC/3 2019, ‘Seeing Race in Biblical Egypt: Edwin Longsden Long’s Anno Domini (1883) and A. H. Sayce’s The Races of the Old Testament (1891)’, Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 28(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.2041-9015.1128 Debbie has put work she is now allowed to share and the introduction to her two books up here: https://lse.academia.edu/DebbieChallis Debbie's recent talk has been recorded and is available: https://events.bizzabo.com/aep/agenda/session/651358 (Registration needed) Other work referenced in the interview: Davies, Vanessa, 2019-20. W. E. B Du Bois, a new voice in Egyptology’s disciplinary history, ANKH. Can download from Academia: https://www.academia.edu/42746258/W._E._B._Du_Bois_a_new_voice_in_Egyptologys_disciplinary_history Gunning, Lucia Patrizio, 2021. Cultural Diplomacy in the acquisition of the head of the Satala Aphrodite for the British Museum. Journal of the History of Collections, fhab025, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhab025. Books with the most influence on Debbie when doing her PhD include Dominic Montserrat (2000) Akhenaten and Digging for Dreams, Ian Hodder and Scot Hudson (2003) Reading the Past. Current Approaches to Interpretation in Archaeology and Sven Lindqvist (1997) ‘Exterminate All the Brutes’. A book that influenced Debbie's writing The Archaeology of Race is Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins (ed.) The Object Reader (2009). The most recent and compelling books that I’ve read using archives, history, politics and objects are Phillippe Sande The Ratline (2020), Dan Hicks The Brutish Museum (2020) and Richard Overy Burning the books. Knowledge Under Attack (2020) James Donaldson is Manager and Curator of the RD Milns Antiquities Museum at the University of Queensland in Australia. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? JD: I see the history of archaeology as a reflective discipline, examining all aspects of archaeological and quasi-archaeological practice over the past several centuries (and perhaps even longer). It has to do with how archaeology used to be done, and how modern archaeology developed, but also with understanding the people who did archaeology and the social, historical and theoretical contexts in which they worked. I’m also interested in the history of formal and informal excavation at particular sites, what happened to the resulting finds, and what we can learn from re-examining those finds and the associated records. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? JD: I research the history of antiquities collecting and collections in Australia, with a particular focus on antiquities collected by Australians during the First World War. My aim is to understand why antiquities were appealing souvenirs for soldiers to bring back to Australia, what kinds of material they were acquiring, and where it is now. Australian service personnel took artefacts from every theatre where they served, from Mesopotamia to the UK, and there is evidence for a diverse range of collecting practices that had a big impact on the way public and private collections of ancient material developed in Australia. There is also the ethical aspect of collecting ancient cultural material during wartime: it is important to consider the relationship between antiquities as souvenirs and their status as items of foreign cultural heritage. A central part of my work is therefore to investigate how artefacts were collected during the war, how these practices relate to the broader context of colonial collecting and antiquarianism in the 19th and 20th centuries, and to promote transparency and dialogue about historical collecting activities and the ethics of antiquities collecting more broadly.

The current repository for this work is the First World War Antiquities Project. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? JD: My undergraduate degree was in Archaeology, but I then studied Classics for my Masters, while working as the manager of our Antiquities Museum at the University of Queensland. I became interested in the history of archaeology through provenance research, and research into the history of the UQ collection. This led to a further interest in how these archaeological collections developed around Australia, and some of the similarities in the way University and other collections were founded and used. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? I’m in the final stages of “Phase One” of the First World War Antiquities Project which has focused on collections from Queensland, including over 60 artefacts from 10 service personnel held by the Queensland Museum in Brisbane. An ongoing project is a biography of JH Iliffe, the first director of the Palestine Archaeological Museum in Jerusalem (now the Rockefeller Museum). Through a strange twist of fate, Iliffe’s archive of personal papers, three antiquities, and over 400 photographs came to be in Queensland and were donated to the University of Queensland’s Fryer Library in 2013. The Antiquities Museum received the artefacts and I curated an exhibition in 2019 on Iliffe’s archive. He spent almost 2 decades in Mandate Palestine in a position of considerable privilege as part of the British administration, and his archive and associated papers present a unique insight into the way Jerusalem was changing at this time, and the role of archaeology and the archaeological museum in these changes. A new project in my role with the RD Milns Antiquities Museum is to start documenting the modern marks on our antiquities collection, inspired by the Artefacts of Excavation project. It promises to be a surprising take on more traditional provenance research and the sources of antiquities held in Australian collections. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? JD: I really enjoyed the challenge of contributing to the first detailed listing of the JH Iliffe collection (based on the UQ Library’s initial accession listing) as part of our recent exhibition. It was a chance to get to grips with a sparsely documented collection, and start to sort out how it all fit together. The collection consists of over 400 photographs, alongside diaries, maps, notebooks and other ephemera, documenting a period of about 40-50 years of Iliffe’s life. It had some structure, but apart from a couple of brief obituaries and a few notes on the backs of photographs, there was very little to go on in terms of bringing order to the collection. It all came down to detective work, both within the collection and outside of it. It was exciting to see the narrative of Iliffe’s life emerge from texts, photographs and diaries, and to find important links to other archives around the world. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. JD: I think my favourite book on the topic is David Lowenthal’s The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge University Press, 1985). It discusses the way the past (including archaeological sites and research) are used, interpreted, preserved, changed and challenged. It is “good to think with” when trying to understand how archaeological finds, sites, evidence and the resulting thing we call “history” has been interpreted, and misused, by all areas of (western) society. Donald Malcolm Reid’s Whose Pharaohs? (University of California Press, 2002) and Contesting Antiquity in Egypt (American University in Cairo Press, 2015) are important syntheses of archaeology, museums, and modern identity in Egypt that bring together a lot of amazing archival material and ephemera that sits outside of “traditional” archaeology but is more in the realm of archaeological reception. I also enjoyed Susan Stewart’s work on collecting and the past in On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Duke University Press, 1993) and am looking forward to reading The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2020). AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? JD: The English poet Francis Brett Young (1884-1954) wrote a poem called “Song of the Dark Ages” in about 1916 while training on Salisbury Plain. He describes digging trenches in the chalk and finding “…calcined human bone: Poor relic of that Age of Stone, Whose ossuary was our spoil.” It goes on to reflect on the passage of time and the futility of the war, ending with the lines “And they will leave us both alone: Poor savages who wrought in stone – Poor savages who fought in France.” I keep coming back to this poem. There is something about this wretched reflection on the futility of the digging, the war, and the passing of time all concentrated on the discovery of ancient human remains that is so striking. Thousands of service personnel passed through Salisbury Plain for training during the war, saw the monuments, and speculated about them. Often this speculation was based on misunderstandings and out-of-date history (one soldier talks about Stonehenge being made by the Romans), but there is something very human about the intersection of archaeology/collecting/souveniring/remembering that I think speaks to why the history of archaeology is an important thing to study. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? JD: I would encourage them not to be afraid to branch out from the established disciplines of archaeology or history or classics. There is so much work in interdisciplinary spaces, like the history of archaeology, but it is sometimes unclear how to get into these areas in standard university programs. Try to cultivate a wide interest in the past and different approaches to it. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? JD: History of archaeology is an emerging discipline in Australia and there is still a lot of foundational work to be done on understanding themes like the development of our old-world archaeological collections, and the history of Australian archaeological missions. There are great untapped archives of materials are universities and museums all around Australia, with links to other work happening around the world. A number of my colleagues are starting to undertake this research so it is an exciting time to be working in this area in Australia. There are also big questions to be asked about how and why “classical” and other forms of archaeology have been done in Australian and how they have contributed to museum collections and our collective understanding of the past. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? JD: I’m mainly active on my Twitter account where I share things related to First World War Antiquities and my work with UQ’s RD Milns Antiquities Museum. You can find me at @CairoJim. My work is also available on my ORDIC profile. Heba Abd El Gawad is an Egyptian Egyptologist and project researcher on the Egypt's Dispersed Heritage project (more information on the project below). She was co-curator of the Beyond Beauty exhibition at Two Temple Place in 2016 and the Listen to Her! exhibition at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology in 2018. We discussed the emotional impact of history of archaeology research, the role of social justice in the history of archaeology, and the ongoing legacies of colonialism. You can listen to our discussion here. The inspirational text Heba mentions in the discussion is by Egyptian geographer Gamal Habdan (1928-1993), a graduate of both Cairo University and the University of Reading. The work Heba refers to is entitled مجموعة شخصية مصر دراسة فى عبقرية المكان 4 أجزاء (The Character of Egypt). The quote from Amelia Edwards' 1877 book A Thousand Miles Up the Nile that Heba references in our discussion is: "I may say, indeed, that our life here was one long pursuit of the pleasures of the chase. The game, it is true, was prohibited; but we enjoyed it none the less because it was illegal. Perhaps we enjoyed it the more" (p.449-450) Heba has provided links to a number of additional project outputs:

Podcasts a) Who owns Egyptian heritage? podcast with Manchester Museum b) Our public panel on the legacies of Western colonialism on ancient Egypt and the link between ancient and modern Egypt chaired by BBC's Samira Ahmed at the National Museum in Scotland listen to this podcast c) You can listen to Heba discussing the Egypt's Dispersed Heritage project and her experience in curation in the latest episode of The Wonder House podcast, published Jan 2021. d) Heba has also been interviewed for the Manchester Museum podcast, published Feb 2021. Social Media Accounts The Egypt Dispersed Heritage project on Twitter and Facebook Comics Webinars: Project partnership with Egyptian comic artists producing Egyptian comic strips and graphic novels to confront colonial legacies of ancient Egyptian displays in Western museums, you can check out our interview with Digital Hammurabi and our comic artists' discussion panel for Everyday Orientalism. Human Remains webinar Your mummies, their ancestors webinar on the ethics of displaying and researching human remains in partnership with Egypt Exploration Society and Everyday Orientalism. Partnerships webpages a) For the Egypt Dispersed Heritage partnership with the Egypt Exploration Society to unpack its colonial legacy check this blog entry b) Project partnership with National Museum in Scotland check this English webpage and Arabic here. Media Coverage: Our project as Arab leading for Digital Comics during COVID 19 https://www.al-fanarmedia.org/2020/08/arabic-comics-reach-a-wider-audience-through-digital-projects/ a) Project in Egyptian Online News Network b) Project Comics in Egyptian Online News Network c) Project on Egyptian National TV Thomas is Curator of the Cyprus Collection at the British Museum. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? TK: In a basic way, it is – or at least should be – just a subsection of the histories of science/exploration/discovery, broadly defined, as well as I suppose of the disciplinary developments within archaeology itself. Tim Murray and others have noted how archaeology has tended to define its own history pretty much from the beginning of its institutional phase in the later 19th century, and has generally been written by archaeologists, so it has generally avoided the same scrutiny as the history of science which has a much broader disciplinary base. At the same time, it’s also a subsection of general imperial and colonial history, especially when carried out in areas that came under imperial and colonial control, and where diggers had explicit agenda – though saying that, the broader urge to explore and record can be found in among naturalists or ethnographers who often were interested in antiquities. More broadly still, it’s the history of ‘encounters’, including within countries where elite collectors and excavators (often local landowners and bigwigs) mapped out nations and controlled their histories through their recording of archaeological remains. One shouldn’t put as much emphasis on the social and political impact or aims/ideology of archaeology as is widespread nowadays, but I think you can represent the history of the subject as a search for origins and identities, but also of change and flux, regardless of where or how this actually happened. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? TK: Mainly 18th to 20th century Cyprus (and the Eastern Mediterranean in the same period more broadly), though working in a British Museum (BM) Mediterranean environment inevitably pans out into broader fields, such as museum procedures and admin – sounds dull, but is interesting (and certainly necessary) as we are very concerned about how we report and reflect our collecting history. I'm also fascinated by the role of the antiquities market in defining museum acquisitions and valorisation of artefacts. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? TK: Like lots of people interested in archaeology, I was fascinated by the history of discoveries, which is probably how a lot of us get into the subject. Ironically, that interest probably waned as I started to study archaeology at university. I remember the lecturer in my first year core archaeology class talking about antiquarians and old archaeological theories, but even if he didn’t like Processual archaeology, he tended to be relatively dismissive of earlier archaeologists. When I was doing my PhD, I saw the history of the subject as a sideshow, and like many just rolled my eyes at what I saw as the ridiculousness of early excavators, such as Luigi Palma di Cesnola. I certainly didn’t realise how important archives were for archaeological purposes, let alone broader historical questions. It was only when I started work at the BM, and began to engage with the subject from within the archive, that I got hooked – first because I realised that you couldn’t understand the collections archaeologically without knowing how they were found and handled, and then more historically in understanding the motivations of early archaeologists. Bit by bit, all the different bits of the subject coalesced into what I hope is a more joined-up interest in the subject. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? TK: I’m finishing a big edition of correspondence relating to various phases of the history of Cypriot archaeology in the 19th century, from the late Ottoman consular activities to the fairly large-scale expeditions of the British Museum. Related to this, I’m also co-working on a paper on a Cypriot antiquarian and collector, Demetrios Pierides, and his relationship to the antiquity market – something that really interests me, as it’s very relevant to modern discussions of the trade. Finally, I’m also involved in a series of workshops on archaeology in the British colonial period in Cyprus with Lindy Crewe, Director of the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute in Nicosia and Anna Reeve, University of Leeds. It had to go virtual, but the benefit is now that you can all join in (www.caari.org/programs). AT: What, from your experience, is the most exciting thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? I think it’s fair to say that as in archaeology itself it’s often more a question of many small discoveries, and eureka moments when things start to connect in a way they didn’t at the beginning. Likewise with finding documents and photographs that you thought were missing, but were simply in a different file. Finding original photographs is always exciting, especially when they show local people – the elephant in the room of the history of archaeology. The edition of correspondence I mention above is joining up lots of individual stories and making sense of things which were very vague at the beginning. One very fun discovery was the Latin-based telegraphic code used by the British Museum’s supervisors in Cyprus to communicate with London. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. TK: I have to be loyal to the books that first inspired me. Henri-Paul Eydoux’s In search of lost worlds (whose original French title, A la recherche des mondes perdus is clearly a play on another far less interesting book!) and Michael Wood’s In search of the Trojan War – I bought this book after seeing the memorable TV show back in the day when a TV company would make a 6 part documentary on one subject! Of more recent titles, I really like Maya Jasanoff’s Edge of Empire, Zeynap Çelik’s About antiquities on Ottoman archaeology, while Jacqueline Yallop’s Magpies, squirrels and thieves is a great read on collecting more generally. Likewise, Karolyn Schindler’s biography of Dorothea Bate, Discovering Dorothea, is great – Bate was primarily a palaeontologist, but her contacts and networks all overlapped with archaeologists and their broader worlds. They all in a sense project a sense of the serendipity and subjectivity, of how much individuals shaped the disciplines (and often went against the social grain). They all have great narratives, which are essential to the subject itself, but especially in engaging broad audiences. I love reading old travel accounts too, even if you have to take a deep breath at the prejudices expressed. One great joy of working where I do is our stunning collection of early books of travel and exploration, especially archaeology, and it’s wonderful to look at them in their glorious original scale and smell. My department has two (!) sets of Richard Pococke’s Description of the East of 1751. It’s a marvel. Conversely, while I won’t name names, but there are also loads of rather mundane chronicles of archaeological discovery out there that leave a lot to be desired. And, lots of writing on the subject is frankly a bit dull, especially when aspiring to being hyper-intellectual. It kind of squeezes the joy out of the subject and leaves potential readers of critical history rather cold. AT: Is there a key object/image/text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? TK: I really love the surviving field notebooks where excavators recorded their finds and began to grapple with what we would now call the ‘discipline of archaeology’. There is one by John Myres where he records the finds from tombs at Amathus in Cyprus a really meticulous way, but at the back are loads of scribbles and thoughts but also an attempt to ‘seriate’ the tombs in order to date them better. Myres has been called the ‘father of Cypriot archaeology’, and you can see his mind working, and the discipline coming into being in front of your eyes. I also love photographs, and one I have in mind shows a large marble capital from Salamis in Cyprus being dragged through the streets of Famagusta in 1891. It shows Royal Navy personnel and lots of local workers, but also the on-looking provide a kaleidoscope of the diverse late Ottoman/early British local community. Oh to have been there…

AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? TK: Reads lots of older archaeological accounts and narratives of discoveries, rather than the many tedious commentaries on them that sometimes pass as historical analysis! You have to read the latter too, but try not to put Descartes before the horse… I think a solid grounding in the history of the region you are interested in is also essential. Things start making sense in an organic way, and you start to realise that archaeology was – in my view – not as important or ideological as is often said in narrow histories of the subject. This would also I think address some of the problems with the lack of knowledge of imperial history that is a big problem today (see next question). Also, develop an interest in biography, micro-history (and related empathetic approaches), and general narrative, but also in the materiality of archival documents – and I think working with archival documents is essential and exciting. Finding an archival niche is I think one of the things that open up the subject and connects with public audiences. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? TK: Well we are all post-colonial now, and there are a lot of discussions mediated through various post-colonial lenses that we have to address, especially the contextualised collection histories of museums and better understanding imperial history. How effective and convincing these discussions are remains moot because I think we tend to jump from very general post-colonial perspectives to very specific archaeological ones without a huge amount of nuance – hence my suggestion that we need to have a very solid grounding in general history. I think we certainly need to address under-representations of archaeological agency – especially gender (cherchez les femmes!) and local communities (from digger and foremen to local elites who collected and studied antiquities – and often collaborated with the acknowledged archaeologists). I think that is one of the key post-colonial insights we can advance with very little effort, just as social historians transformed how we saw history ‘at home’ in past decades. Global knowledge justice is certainly our remit too – the recent lockdown simply reinforced the problem of access to archives (and collections). I think if we could open up our archives in a digital way that would address some of the problems. Saying that, I think we also need to expand the public awareness of archaeological and museum histories far beyond present conceptions. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? TK: Despite what I said about the importance of digital, I don’t tweet or blog! You might find random visual musings on Instagram which I like to imagine as archaeological Wombling (nebulatrope). Maddy Pelling is an art historian specialising in the history of archaeology and collecting in the 18th and early 19th centuries. She is currently working on a postdoctoral project on the history of women antiquarians in the UK during this period. We discuss the evidence for women excavating, researching and publicising the material culture of the past, and the importance of local contexts, identity and colonialism in the history of archaeology. Listen to our conversation here. Follow Maddy on twitter @maddypelling.

Read Maddy's comments on the excavations at Warminster in the online edition of Vestuta Monumenta. Listen to Maddy's paper, "Digging Up the Past: Contested Territories and Women Archaeologists in 1780s Britain and Ireland" at the Open Digital Seminar in 18th Century Studies. Further Reading/References Lake, Crystal. 2020. Artifacts: How We Think and Write About Found Objects. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Raiders of the Lost Past with Janina Ramirez: The Sutton Hoo Hoard (BBC4) Dr Gabriel Moshenska is a Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? GM: I think there’s different ways of approaching this question. There’s no single history of archaeology, just as there is no one best approach to its study. I’m particularly fascinated by biographical approaches – individual, group, and object-focused biographies. History of archaeology can rise up from the grassroots – sites, artefacts, archives, balance sheets, individuals, institutions – or it can descend from the clouds of theory, and trace concepts and models onto the crooked timber of archaeological humanity. I like the diversity of it, even if I’m rather unimpressed with quite a lot of the work that takes place within that diversity. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? GM: Primarily, I’m engaged in a biographical study of Thomas Pettigrew, the surgeon-antiquarian who became well known for holding public unrollings of Egyptian mummies. I’m assembling his intellectual biography in fragments, and currently looking at his work as librarian to the Duke of Sussex, and the liberal political milieus that this brought him into contact with. I have other strands of interest as well – perhaps too many – including the history of archaeology in London, from Charles Roach Smith through to the present. Through my Pettigrew work I’ve become very interested in the early history of the British Archaeological Association, and the rise of archaeology as a bourgeois pastime in the mid-nineteenth century. Most recently I did some work looking at the history of protest movements at archaeological excavations, and the nature of public ‘save the heritage’ campaigns, that often come to regard archaeologists as their enemies. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology?

GM: During my PhD I became very interested in the epistemological significance of eye-witnessing in archaeology, and the role of expert and amateur audiences at excavations. This led me into historical studies of public archaeology, including Pettigrew’s mummy unrollings. Then I started working on archived correspondence of archaeologists and antiquarians, and there was no going back. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? A long-overdue book! I’m also wrangling with the late Peter Gathercole’s research notes on Gordon Childe, which contain a wealth of fascinating material. Related to this, lately I’ve been enjoying Katie Meheux’s penetrating and illuminating work on Childe. AT: What, from your experience, is the most exciting thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? Correspondence between two antiquarians – Robert Lemon and Thomas Pettigrew – from 1826. Lemon reported to Pettigrew that he’d discovered a long-lost theological work by John Milton in the State Paper Office. Knowing sod-all about Milton, and having no wifi in the British Library manuscript room at that point, my first thought was blimey, what a discovery! Does anybody know about this? Fortunately the existence of De Doctrina Christiana is well known, but I was able to add a few details to the history of its rediscovery and attempts to variously authenticate and debunk it, and publish a short paper in Milton Quarterly. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? GM: I very much enjoyed From Genesis to Prehistory, Peter Rowley-Conwy’s book on the contested reception of the three age system, it struck a lovely balance between the big ideas and the people behind them, and it was very well written. Philippa Levine’s The Amateur and the Professional is a book I return to again and again in my work, with ever growing appreciation for its breadth of understanding of Victorian antiquarianism. In terms of fascinating subject matter and superlative prose, The Master Plan, Heather Pringle’s study of Nazi archaeology, is unmatched. I highly recommend it to all archaeologists, particularly those naïve fantasists who cling to the idea of an ideology-free science of archaeology. AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? GM: One of the strangest episodes in Thomas Pettigrew’s career was his mummification of the tenth Duke of Hamilton in 1852. Pettigrew carried out the embalming in the traditional Ancient Egyptian manner, and conducted a full faux-Egyptian funeral service, after which the Duke’s remains were interred in a genuine Egyptian sarcophagus. I read a letter from the Duke’s valet to Pettigrew in the Beinecke Library that said (I’m paraphrasing obviously) ‘The Duke just died, please come and bring the embalming spices’. I was and remain fascinated by the disparity between the outlandish strangeness of the event, and the banal matter-of-factness of the letter that heralded it. Thinking about this helps me keep the sense of wonder in my research, and a reminder not to feel too familiar or comfortable with the people and events that I’m studying. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? GM: There is so much still to do, so much incredible material lying untouched in archives. Don’t stick too closely to what’s been done before – blaze a new train through the sources and the ideas. And for god’s sake, read deeply in the historiography of science so you don’t make a fool of yourself. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? GM: The poverty of historiography. The huge amount of published research which is sub-antiquarian dross, boot-licking hagiography, or unoriginal piffles-about in stale secondary sources. We often talk about archaeology as a tool of European imperialism, but I think there’s a great deal more to be done looking at the details and operations of this mechanism. For example, I would love to know more about the roles of British archaeologists in colonial expeditions, invasions, and punitive raids. __ Follow Gabe on twitter at @GabeMoshenska or email him and ask for pdfs. |

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed