|

Dr Julie Holder is currently a Tutor at the University of Glasgow and has been teaching on History, Economic and Social History, and Museum Studies modules. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? JH: I think it is very difficult to clearly define the history of archaeology, especially as so many different disciplines work with material culture and the history of societies of the past. My own research looked at nineteenth-century antiquarianism, which has traditionally been seen as the precursor to systematic and scientific methods of archaeological practice. However, during the nineteenth century the study of ‘antiquities’ included objects, monuments and manuscripts, with scholars focusing on the history of society, culture and civilisation from prehistoric to historic periods. Throughout my PhD I was constantly thinking about whether there is a difference between historical archaeologists and material culture historians. I do not think there is an answer, as every person has a different perspective and the ambiguity and interdisciplinarity in these fields prompts researchers to keep asking new and interesting questions of their sources. From my own work, I would define the history of archaeology as the study of the development of scholarship which focuses on material culture and the history of society, whether this is through excavation, material culture analysis, or the study of objects and culture through manuscript research, and that the history of archaeology also includes how objects were collected and displayed in private collections and museums. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? JH: I recently completed my thesis titled ‘Collecting the Nation: Scottish History, Patriotism and Antiquarianism after Scott (1832-91)’, which critically examined the interface between the expansion of the Scottish historical collection in the museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and the development of modern Scottish historiographical practices. My research analysed the relationships between collecting, representing, and writing about the Scottish past from 1832 to 1891, and considered the intersections between antiquarianism, Scottish history, material culture studies, archaeology, collecting practices, and museum development in the nineteenth century. Although my research focused on Scotland, I also compared museums across the British Isles, which I found really interesting for considering similarities and differences in methods of classification and display. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? JH: I originally did an MLitt in Museum and Gallery Studies at the University of St Andrews, and it was while I was doing my dissertation that I became interested in the history of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, their museum, and the history of archaeology and material culture research. My dissertation examined the motivations behind the acquisition of 100 ‘folk art’ objects from different parts of Scandinavia, currently held by National Museums Scotland. I then successfully applied for an AHRC-funded collaborative PhD at the University of Glasgow and National Museums Scotland as detailed above. It was during my PhD research that I really started to appreciate how the development of archaeological ideas and methods had a significant influence on the expansion and study of the Scottish historical collection in the museum. It was thought-provoking to see how perceptions on the value of material culture as a primary source also affected whether objects were used (or not) in nineteenth-century national histories of Scotland and how an increased interest in studying historical objects prompted the emergence of a separate body of material culture histories. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? JH: I am currently working on converting my thesis into separate articles, one of which has been accepted for publication and will be available November 2022. I am also working on an essay for an edited volume that looks at the ways in which objects connected to Mary Queen of Scots were displayed and interpreted in the nineteenth century. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? JH: Really getting to know the people behind the history of archaeology. The networks of influence and the social nature of antiquarian and archaeological societies was really important to how material culture studies developed. This was not only within Scotland, but through connections with other antiquaries and museums around the world. The first thing I did at the beginning of my PhD was read through 60 years of the Society’s minute books and it was like being immersed in a favourite soap opera. I think the human friendships, rivalries, arguments and fallibilities that underpinned the development of archaeological ideas and approaches is the most meaningful thing that I have come across as it gave the social context to ideological developments. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. JH: For anyone interested in the history of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland the edited collection A. Bell (ed) The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition is an essential go to. I cannot even count how many times I have come back to this text to check details and information. Rosemary Sweet’s Antiquaries: The Discovery of the Past in Eighteenth-Century Britain was a key text for me during my MLitt and when I started my PhD, and Sweet’s current research extends into nineteenth-century antiquarianism. Sweet’s work demonstrates how modern history, archaeology, and cultural history have their foundation in antiquarian ideas and approaches. Susan Pearce’s Museums, Objects and Collections has been a text that I have gone back to again and again and is great for those thinking about the relationship between objects, museums and interpretation. AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting?

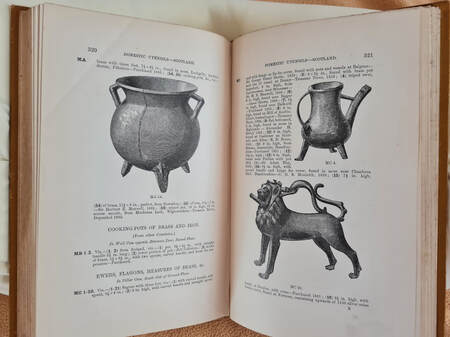

JH: The 1892 Catalogue of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland has been a text that has been essential to my research, and I keep revisiting. It contains so much detail on objects, donors, acquisition dates, and also uses the numbering still in use by NMS allowing me to identify objects and locate them in the museum. During lockdown, when the archives were closed, I managed to acquire my own copy of the catalogue that had previously been the property of Reverend Cecil Vincent Goddard, who collected on behalf of the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford. I still haven’t had to time to have a good look through his notes and additions. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? JH: Do not let yourself be impeded by notions of disciplinary boundaries. There are so many people who were important to the development of archaeology and material culture studies who have traditionally been left out of histories of the discipline as they have not been previously defined as archaeologists; their histories need to be told too. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? JH: Redefining who should be included in a history of archaeology and making sure the stories of those who have been excluded in the past are given greater attention. It is great to see the establishment of Beyond Notability as a project that will start addressing this issue for expanding scholarship on the history of women in archaeology. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? JH: My Twitter account is @Julieh80 Blog posts Women collectors, Lady Associates and the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland – History Journal https://mqs.glasgow.ac.uk/index.php/2020/08/18/the-multiple-meanings-of-the-queen-mary-harp/ https://blog.nms.ac.uk/author/jholder/ |

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed