|

Sarah is Lecturer in modern Middle Eastern history at Staffordshire University. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? SI: I’m not sure I’m properly a historian of archaeology – I’m more of an interloper who uses historical records of archaeology to look at social and gender history – so I’m not sure it’s entirely my place to define it. But from my perspective it’s the history of how archaeological and the search for material remains of human activity is carried out, not just by professionals in the field but also in terms of its relationships with the people surrounding it – labourers, farmers on archaeological land, guards and museum attendants, people who read about and watch films of archaeology, interact with it in exhibitions and in discussions… and so on. AT What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? SI: I primarily look at the role of ordinary Palestinians and other people from the Levant region in the conduct of archaeology in Late Ottoman and Mandate Palestine. This ranges from educated Christian Lebanese who worked at supervisors on excavations for the Palestine Excavation Fund for many years and who became quite significant figures in how the archaeology of their period was enacted and interpreted, to women and men from nearby villages who were manual labourers on excavations, perhaps only for a total of a few months, or to some of the (usually but not always) nameless guards and other workers who were employed by the Department of Antiquities of the British Mandate administration in Palestine, or the lower-level dealers and go-between from the Palestinian Syriac Orthodox community who were the conduit by which various museums acquired the Dead Sea Scrolls. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? SI: In a parallel universe I went to university nearly 30 years ago and stuck with the archaeology I started then. In actual fact the course at Cambridge bored me so badly that I switched to anthropology – I should have stood up to my school better and gone to Sheffield, but who makes good decisions at 18? I went back to university to do a PhD in my late 30s and became a social historian of Palestine, but by various roundabout routes (involving looking for something completely different in the archives of the PEF) I’ve ended up combining the two in a lot of my work. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? SI: Although my main research project at the moment isn’t history of archaeology – it’s on the 1927 earthquake in Palestine, so it does still have overlaps with the material environment and how that affects history – I am working on a couple of papers in HoA. One is for a conference next spring run by Michael Press at Agder University, for which I’ll be looking at the sale of antiquities, including Dead Sea Scrolls jars, by the Department of Antiquities/Palestine Archaeological Museum in the Mandate and Jordanian periods. I also have an article coming out in Jerusalem Quarterly taking a long-view look at the lives and working conditions of guards on archaeological sites in the Mandate period, especially at Athlit and Jericho, and how those intersect with the broader political situation in the country, and I’ll be speaking on the same broad subject at a Bade Museum/PEF online talk later this month. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? SI: The archives from the pre-WWI Harvard University excavations at Sebastia, which are at the Harvard Semitic Museum, include the fortnightly pay lists, which means they have long lists of the names of every worker on the site, men and women, how many days they worked during that period, and how much they were paid. Given how little we know about the lives of ordinary Palestinians over a century ago, how much information has been lost in the wars since, and how many Palestinians have been displaced as refugees, to able to get that snapshot of what such a large group of people were doing is amazing. Archaeological records aren’t often on the radar of social historians but sometimes they can be amazingly rich sources. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. SI: Given my subject area, the main ones would be other explorations of workers on archaeological sites, so Stephen Quirke’s Hidden Hands: Egyptian Workforces in Petrie Excavation Archives, 1880–1924, parts of Elliott Colla’s Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity and Donald Malcolm Reid’s books Contested Antiquities in Egypt: Archaeologies, Museums and the Struggle for Identities from WWI to Nasser and Whose Pharaohs? Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to WWI, and of course Amara Thornton’s investigations of archaeology in Palestine during the Mandate period. Going beyond books, I’d also like to flag up Unsilencing the Archives[https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/9eb391c6f57f4399a58ecf9b818e6762], an online exhibition curated by Melissa Cradic and Samuel Pfister, which is an amazing look at the workers at Tel en-Nasbeh during the Mandate period and which includes video footage from the late 1920s of archaeological labourers at work. AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? SI: There is a photograph in the PEF archives of two Palestinian women at the Tel Jezar site, I think during R.A.S. Macalister’s excavations there, sieving for small finds. One of them is looking straight into the camera. She’s mid-work, sitting on the earth, staring at us with a really no-bullshit look on her face. She’s just as much part of the history of archaeology as a guy in a pith helmet and puttees whose name is on all the publications about Gezer, and I want to know as much as I can about her life. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology?

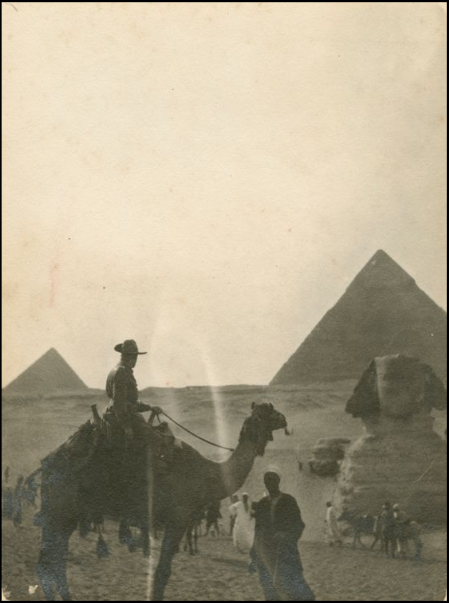

SI: The best information is never where you expect to find it. To amend a well-known saying, the best way to make the Gods laugh is to tell them your (research) plans – my most exciting finds have always been accidents, usually when I’m looking for something completely different. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? SI: I would say that getting away from the Indiana Jones/dead white men view of archaeology is one of the biggest things – especially decolonisation, but also finding the female, black, Muslim, gay, Arab, Asian, indigenous, non-literate, working-class etc etc people who contributed to archaeology but whose names aren’t in the published records. And moving on from that, communicating this so that the public view of archaeology (and perhaps even more the view of TV producers) evolves away from treasure and ‘exploration’ to some more nuanced understandings of who does/did archaeology, why, and what its impacts were for their lives and communities. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? SI: I rant a lot on twitter at @DrTermagant, and am less ranty on my project twitter handle at @JerichoQuake27. Otherwise, my profile page on the Staffordshire University website (when that goes up) should list publications and have access to those which are open access, and have information on my current research. James Donaldson is Manager and Curator of the RD Milns Antiquities Museum at the University of Queensland in Australia. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? JD: I see the history of archaeology as a reflective discipline, examining all aspects of archaeological and quasi-archaeological practice over the past several centuries (and perhaps even longer). It has to do with how archaeology used to be done, and how modern archaeology developed, but also with understanding the people who did archaeology and the social, historical and theoretical contexts in which they worked. I’m also interested in the history of formal and informal excavation at particular sites, what happened to the resulting finds, and what we can learn from re-examining those finds and the associated records. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? JD: I research the history of antiquities collecting and collections in Australia, with a particular focus on antiquities collected by Australians during the First World War. My aim is to understand why antiquities were appealing souvenirs for soldiers to bring back to Australia, what kinds of material they were acquiring, and where it is now. Australian service personnel took artefacts from every theatre where they served, from Mesopotamia to the UK, and there is evidence for a diverse range of collecting practices that had a big impact on the way public and private collections of ancient material developed in Australia. There is also the ethical aspect of collecting ancient cultural material during wartime: it is important to consider the relationship between antiquities as souvenirs and their status as items of foreign cultural heritage. A central part of my work is therefore to investigate how artefacts were collected during the war, how these practices relate to the broader context of colonial collecting and antiquarianism in the 19th and 20th centuries, and to promote transparency and dialogue about historical collecting activities and the ethics of antiquities collecting more broadly.

The current repository for this work is the First World War Antiquities Project. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? JD: My undergraduate degree was in Archaeology, but I then studied Classics for my Masters, while working as the manager of our Antiquities Museum at the University of Queensland. I became interested in the history of archaeology through provenance research, and research into the history of the UQ collection. This led to a further interest in how these archaeological collections developed around Australia, and some of the similarities in the way University and other collections were founded and used. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? I’m in the final stages of “Phase One” of the First World War Antiquities Project which has focused on collections from Queensland, including over 60 artefacts from 10 service personnel held by the Queensland Museum in Brisbane. An ongoing project is a biography of JH Iliffe, the first director of the Palestine Archaeological Museum in Jerusalem (now the Rockefeller Museum). Through a strange twist of fate, Iliffe’s archive of personal papers, three antiquities, and over 400 photographs came to be in Queensland and were donated to the University of Queensland’s Fryer Library in 2013. The Antiquities Museum received the artefacts and I curated an exhibition in 2019 on Iliffe’s archive. He spent almost 2 decades in Mandate Palestine in a position of considerable privilege as part of the British administration, and his archive and associated papers present a unique insight into the way Jerusalem was changing at this time, and the role of archaeology and the archaeological museum in these changes. A new project in my role with the RD Milns Antiquities Museum is to start documenting the modern marks on our antiquities collection, inspired by the Artefacts of Excavation project. It promises to be a surprising take on more traditional provenance research and the sources of antiquities held in Australian collections. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? JD: I really enjoyed the challenge of contributing to the first detailed listing of the JH Iliffe collection (based on the UQ Library’s initial accession listing) as part of our recent exhibition. It was a chance to get to grips with a sparsely documented collection, and start to sort out how it all fit together. The collection consists of over 400 photographs, alongside diaries, maps, notebooks and other ephemera, documenting a period of about 40-50 years of Iliffe’s life. It had some structure, but apart from a couple of brief obituaries and a few notes on the backs of photographs, there was very little to go on in terms of bringing order to the collection. It all came down to detective work, both within the collection and outside of it. It was exciting to see the narrative of Iliffe’s life emerge from texts, photographs and diaries, and to find important links to other archives around the world. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. JD: I think my favourite book on the topic is David Lowenthal’s The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge University Press, 1985). It discusses the way the past (including archaeological sites and research) are used, interpreted, preserved, changed and challenged. It is “good to think with” when trying to understand how archaeological finds, sites, evidence and the resulting thing we call “history” has been interpreted, and misused, by all areas of (western) society. Donald Malcolm Reid’s Whose Pharaohs? (University of California Press, 2002) and Contesting Antiquity in Egypt (American University in Cairo Press, 2015) are important syntheses of archaeology, museums, and modern identity in Egypt that bring together a lot of amazing archival material and ephemera that sits outside of “traditional” archaeology but is more in the realm of archaeological reception. I also enjoyed Susan Stewart’s work on collecting and the past in On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Duke University Press, 1993) and am looking forward to reading The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2020). AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? JD: The English poet Francis Brett Young (1884-1954) wrote a poem called “Song of the Dark Ages” in about 1916 while training on Salisbury Plain. He describes digging trenches in the chalk and finding “…calcined human bone: Poor relic of that Age of Stone, Whose ossuary was our spoil.” It goes on to reflect on the passage of time and the futility of the war, ending with the lines “And they will leave us both alone: Poor savages who wrought in stone – Poor savages who fought in France.” I keep coming back to this poem. There is something about this wretched reflection on the futility of the digging, the war, and the passing of time all concentrated on the discovery of ancient human remains that is so striking. Thousands of service personnel passed through Salisbury Plain for training during the war, saw the monuments, and speculated about them. Often this speculation was based on misunderstandings and out-of-date history (one soldier talks about Stonehenge being made by the Romans), but there is something very human about the intersection of archaeology/collecting/souveniring/remembering that I think speaks to why the history of archaeology is an important thing to study. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? JD: I would encourage them not to be afraid to branch out from the established disciplines of archaeology or history or classics. There is so much work in interdisciplinary spaces, like the history of archaeology, but it is sometimes unclear how to get into these areas in standard university programs. Try to cultivate a wide interest in the past and different approaches to it. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? JD: History of archaeology is an emerging discipline in Australia and there is still a lot of foundational work to be done on understanding themes like the development of our old-world archaeological collections, and the history of Australian archaeological missions. There are great untapped archives of materials are universities and museums all around Australia, with links to other work happening around the world. A number of my colleagues are starting to undertake this research so it is an exciting time to be working in this area in Australia. There are also big questions to be asked about how and why “classical” and other forms of archaeology have been done in Australian and how they have contributed to museum collections and our collective understanding of the past. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? JD: I’m mainly active on my Twitter account where I share things related to First World War Antiquities and my work with UQ’s RD Milns Antiquities Museum. You can find me at @CairoJim. My work is also available on my ORDIC profile. Martyn is Senior Researcher in the Aerial Investigation and Mapping team, Historic England. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? MB: I’m not sure that I’d want to… I think it’s more important to recognise that every aspect of modern archaeological practice has a history, and that history is more likely than not to be messy, complex, and not confined to the archaeological literature. And, of course, that history isn’t disconnected from the present. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? MB: The main things currently are (i) the various archives (and other sources) relating to OGS Crawford; (ii) the history and development of aerial archaeology; and (iii) the history of Stonehenge and its landscape. The Venn Diagram would show considerable overlap between these three, and of course, there’s a potentially vast range of topics covered by them. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? MB: I think this goes back to my undergraduate days at Birmingham, and reading things like Chris Chippindale’s Stonehenge Complete, then still in its first edition (does he regret the title?), alongside Shanks & Tilley’s Re-Constructing Archaeology and Social Theory and Archaeology. More important, though, was one of the bits of coursework we were required to do - detailed survey of the history and archaeology of your home parish, and I realised I quite enjoyed digging in to the lives and times of the various obscure antiquarians and their curious ways. Some weird stuff happened in Westgate-on-Sea. Probably still does. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? MB: Always… There are several things ongoing (does mentioning them here commit me to finishing them?). With Crawford, there are many topics vying for attention – at present, I’m primarily interested in the earliest (pre-1920) stages of his archaeological career, especially the influence of Oxford-taught geography and anthropology on his ideas about prehistory. I’m also interested in his unofficial advisory role with Phoenix Press in the 1950s, in which he essentially had power of veto over publication proposals for books on archaeology, anthropology and history. He was paid mainly in cigars. As far as Stonehenge is concerned, I’m mainly interested in various goings-on during the later 19th century, a period that has been misrepresented somewhat in many of the main texts covering the period. I’m also working through the various myths that have emerged over the last 100 years or so (no, the RAF didn’t ask for the stones to be knocked down; no, you couldn’t hire a hammer to chip bits off the stones; etc), which might sound a tad frivolous, but the reasons for their emergence and persistence are closely tied to particular narratives about Stonehenge, especially in relation to questions of ownership and access. With aerial photography, the later 19th century again remains a period of particular interest. Thanks to a stroke of good fortune, some of the earliest surviving aerial photographs taken over England (by Cecil Shadbolt between 1882 and 1890) are now in the Historic England Archive at Swindon, so I hope to be taking a closer look at what he was up to. That’s going to have to wait until I can get to the British Library, among other places, again. AT: What, from your experience, is the most exciting thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why?

MB: Viewing the Shadbolt collection of photographs (actually his own set of glass lantern slides for use in public lectures) for the first time was particularly memorable. He was a key figure in the early days of photography from balloons, but when I wrote A History of Aerial Photography and Archaeology (publ. 2011) I couldn’t track down any of his photographs, and had only seen two reproduced in print. This collection contained 27, all but one taken over London. They appeared a few years ago at an auction house just down the road from the HE Swindon office, still in Shadbolt’s own wooden slide-box. As an aside, can I encourage everyone to try to stop automatically putting the words ‘hot air’ in front of the word ‘balloon’. Think gas instead. Many of the more memorable things I’ve seen came to my attention because someone else had spotted them first and told me about them. With the Shadbolt slides, it was my (now retired) colleague Ian Leith. Collections like that seldom escaped his attention. It was a similar case with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings’ (SPAB) files on Stonehenge. My colleague Rebecca Lane mentioned these to me when we were working on the Stonehenge Landscape project at English Heritage (now Historic England), which was published as The Stonehenge Landscape (Bowden et al 2015). Rebecca was looking at some of the more interesting buildings in the World Heritage Site, but the SPAB files related specifically to Stonehenge itself, and mainly to the period from c1890-1902. They included correspondence from the likes of Pitt Riversand Philip Webb, and underlined the extent of the Arts & Crafts influence on the third Sir Edmund Antrobus’ custodianship of Stonehenge and on the 1901 ‘restoration’ work, including William Gowland’s excavations. Some of this is discussed in Restoring Stonehenge… As far as I can tell, they hadn’t been cited before – the involvement of architects at Stonehenge has been a bit of a blind spot as far as the archaeological history of the site is concerned. Detmar Blow, the architect who was actually in charge on site in 1901, is seldom if ever mentioned in accounts of Gowland’s work, and while the latter’s report (published in Archaeologia in 1902) is frequently referred to, Blow’s report, also published in 1902, wasn’t cited in an archaeological publication until Bowden et al 2015. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. MB: Adam Stout’s Creating Prehistory and Kitty Hauser’s Shadow Sites (as well as her Crawford biography Bloody Old Britain) are books I’d happily recommend to anyone interested in the history of British archaeology, and particularly prehistory and aerial archaeology, prior to WW2. In fact, everyone should read them, whatever your interests, Another book I’m always surprised that many people don’t know about is Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s Objectivity. As the blurb says, ‘Objectivity has a history, and it’s full of surprises’. No home should be without it. AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? MB: There are plenty, but the one that springs immediately to mind is a letter in the Crawford archive at the Bodleian which he wrote while a PoW at Holzminden in 1918. Scrawled in tiny handwriting on thin paper, it was smuggled out by one of the men who took part in the famous tunnel escape. In it, Crawford refers to another letter sent to his friend, the archaeologist Harold Peake, which apparently contained a code to use in future ‘official’ correspondence between the two. Unfortunately, that letter does not survive. Peake’s subsequent letters to Crawford do… I haven’t spotted anything yet. I think it was Kitty Hauser who suggested that the use of code might explain why Peake’s letters are so dull. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? MB: Plenty of good advice has been offered so far by others in this series. I think the main thing I’d add is the need to be prepared to look well beyond the archaeological archives and literature – I’ve seen too many articles where the focus is incredibly narrow. For instance, understanding Crawford’s work and its influence requires delving into Victorian and Edwardian geography and anthropology, disciplines with their own traditions and histories of practice. With Stonehenge in the 19th century, contemporary art, literature, newspapers and magazines are essential sources but again, they’re not things that can be quickly dipped in to for the extraction of key ‘facts’. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? MB: I think I’d just reiterate the point about everything having a history – I read too many books and articles that refer to ideas, interpretations, practices etc without any apparent acknowledgement of this. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? MB: I try to make sure everything I publish or contribute to is accessible in some form or other at, or via, Academia.edu. Personal twittering occurs @MartynBarber2, and I am also responsible for some of the posts emanating from the @HE_Archaeology account, mainly the ones with aerial photos in. Publications mentioned: Barber. M (2011) A History of Aerial Photography and Archaeology. Mata Hari’s Glass Eye and Other Stories(English Heritage: Swindon) Barber, M (2014) ‘Restoring’ Stonehenge 1881-1939 (English Heritage Research Report 6/2014) https://research.historicengland.org.uk/Report.aspx?i=15238 Blow, D (1902) The Architectural Discoveries of 1901 at Stonehenge. Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, 3rd Series vol 9, 121-142 Bowden, M et al (2015) The Stonehenge Landscape. Analysing the Stonehenge World Heritage Site(Historic England: Swindon) Chippindale, C (1983) Stonehenge Complete (1st ed, Thames & Hudson: London) Daston, L & P Galison (2010) Objectivity (Zone Books: Brooklyn) Gowland, W (1902) Recent Excavations at Stonehenge. Archaeologia vol 58 (1), 37-118 Hauser, K (2007) Shadow Sites: Photography, Archaeology, & the British Landscape 1927-1955 (Oxford University Press: Oxford) Hauser, K (2008) Bloody Old Britain. OGS Crawford and the Archaeology of Modern Life (Granta: London) Lane, R (2011) Stonehenge World Heritage Site Landscape Project: Architectural Assessment (English Heritage Research Report 42/2011) https://research.historicengland.org.uk/Report.aspx?i=14994 Shanks, M & C Tilley (1987) Social Theory and Archaeology (Polity Press: Cambridge) Shanks, M & C Tilley (1987) Re-Constructing Archaeology: Theory and Practice (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge) Stout, A (2008) Creating Prehistory: Druids, Ley Hunters and Archaeologists in Pre-war Britain (Blackwells: Oxford) |

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed