|

Dr Artemis Papatheodorou is an Early Career Fellow in Hellenic Studies 2023-2024, Harvard University. Interview with Network Coordinator Dr Amara Thornton. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? AP: The history of archaeology is a different kind of digging than what you do in an ancient site. Historians of archaeology are after the links between the material remains of distant pasts and population groups that lived in comparatively less distant pasts, be they nations, elites, ordinary people, excavation workers, women, trained and amateur archaeologists, etc., or even institutions, such as museums or the League of Nations. They study archival documents, publications, photographs, videos and other mostly written or audiovisual primary sources in order to decipher the reception of antiquities by such people and institutions, the meanings and values that these ascribed to ancient finds, the uses they made out of antiquities, and the purposes of such uses. It is a particularly diverse field that brings together many different sources, techniques, theoretical approaches, even disciplines. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? AP: I specialize in the history of archaeology, heritage and the classical reception in the Ottoman long 19th century. I look extensively into primary sources in Ottoman Turkish and Greek, and this allows me a close-up both to the Ottoman state and Ottomans writing in the official language of the state on the one hand and (Ottoman) Greeks in all their diversity on the other hand. This means that I can also read Karamanlidika, that is, Turkish written with the Greek alphabet, a linguistic hybrid used mostly by the Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox in Cappadocia. Moreover, I speak French, the lingua franca of the long 19th century, and this too opens up new vistas in my research. In my work I make sure to study mainstream actors and topics as well as lesser known aspects in the history of archaeology, such as the reception of antiquities by ordinary (i. e. non-elite) Ottoman Greeks. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? AP: I had questions and I couldn’t get satisfactory answers! So, I had to look for answers myself. This applies primarily to Ottoman history, which is my broader field of expertise. But then, once into Ottoman studies, I had to decide among a few topics of special interest for my PhD. I had always been fascinated by antiquities. As a child growing up in Greece, Antiquity and its material remains formed part of my daily life. Roads were named after ancient or medieval locations, I was aware that the Athenian suburb where I lived was where Euripides had his house in ancient times, and the local newspaper covered archaeological discoveries made during the construction of houses in our area. Also, the Near and Middle East, which I hold dear in my heart, is not simply rich in antiquities. Antiquities are central to understanding important aspects of the cultures and identities formed in the region. For example, look at the Ottoman Greeks and their interest in the classical and Byzantine past. Or the Lebanese and the Phoenicians. The importance of Islamic monuments for Arabs. Or the value that Turks ascribe to prehistoric finds, among other. And at the same time, this region became a hotspot for Europeans and Americans looking for the roots of their culture. To me, the history of archaeology has been a unique gateway to understanding the Ottoman Empire in its last phase as a multi-layered crossroads of peoples, identities, ideas and practices. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now?

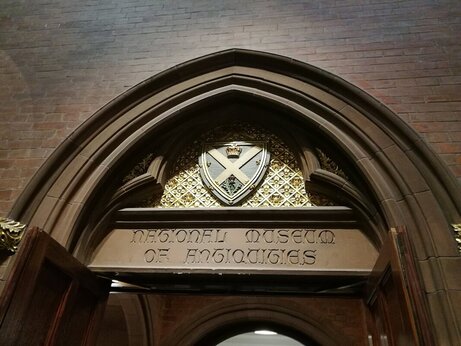

AP: Until recently, as post-doctoral research fellow at the Research Centre for Anatolian Civilizations (ANAMED, Koç University), I worked on a project on the reception of antiquities by ordinary Ottoman Greeks in the last decades of the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia. In the history of archaeology, we still seem to privilege the educated elites over ordinary people, and for this reason this project has been of special importance to me. Moreover, as the archive I worked on is a collection of testimonies by Ottoman Greeks after they settled in Greece as refugees, trauma permeates what they convey to us. This adds some very interesting layers of analysis in the history of archaeology, and actually turns the history of archaeology into a vehicle for understanding broader questions besides the reception of antiquities stricto sensu. In the academic year 2023-2024, I dedicate some time to the study of the reception of Byzantium by Ottoman Muslims. My starting point is a book in Ottoman Turkish on Kariye Mosque, that is, the Chora Monastery in Constantinople published in 1910. The book in question is an art historical treatise dating from a very interesting period for Byzantine monuments in the Ottoman capital. My main project however is the reception of Alexander the Great by the Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox in Cappadocia in the 19th century. This is more of a classical reception project, but the classical reception informed the interest of local people on antiquities back then. Although we know a lot about Alexander the Great in western traditions and in the persianate world, we know close to nothing about how his legend affected the Turkish-speaking but Greek Orthodox Cappadocians, a minority that by means of its language (Turkish) and religion (Greek Orthodox) stood between two worlds, the Ottoman Turkish and the Greek ones. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? AP: There are so many… But one of the things that I enjoy the most and in which I find meaning is the host of voices that have been developed over the years in history of archaeology research. History of archaeology is a field that invites research work not only by historians but also by experts originating in other disciplines, including archaeologists, art historians, conservators, and architects. It thus becomes a ground for extraordinary cross-fertilizations and dialogue. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. AP: One of my favourite books in the history of archaeology is “Scramble for the Past” (Bahrani et.al. (eds.), SALT, 2011). It brings together many aspects related to archaeology in the Ottoman domains in the long 19th century, and when it first came out it broke new ground in the way we approach Ottoman archaeological history. Even more than 10 years after its publication, it remains relevant. AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? AP: I very much like the logo of the Imperial Museum, that is, the Ottoman archaeological museum in Constantinople. It is in Ottoman Turkish and reads as “Müze-i Hümayun” in what seems to me to be Gothic fonts. I can spend a long time just looking at its two words and trying to think of how it might have been created in the first place: the discussions about having a logo, the choice of font, any changes requested and the final approval, its first ever use. It survives as letterhead in the official correspondence of the Museum and in its period publications. Perhaps elsewhere too… AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? AP: Always be aware that what you will work on is but a minuscule part of a vast area of past human activity. Be open to the new and the unexpected, and ready to challenge your very own assumptions. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? AP: I believe that we need to continue working on the elites, because formal archaeology was after all an elite activity, but at the same time systematically provide more space to ordinary people, women, and locals who engaged with antiquities within or without a formal archaeological context. Their views are no less valuable and consequential than the ones of those who happened to be privileged at a specific time in history. Also, provenance research is important and can help tackle issues that go beyond the strictly academic type of inquiry. It is a bridge between the study of culture and the actual formation of culture. Provenance research can help us decide in what kind of a society we want to live, and what kind of relations we want to have we the rest of the world. This is valid not only for former colonialist powers that collected antiquities from other countries oftentimes by taking advantage of their superior might, but also for countries of origin that have largely shaped their identity as being sole guardians of heritage in their lands. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? AP: You can follow me on academia.edu or ResearchGate: https://harvard.academia.edu/ArtemisPapatheodorou https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Artemis-Papatheodorou Dr Julie Holder is currently a Tutor at the University of Glasgow and has been teaching on History, Economic and Social History, and Museum Studies modules. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? JH: I think it is very difficult to clearly define the history of archaeology, especially as so many different disciplines work with material culture and the history of societies of the past. My own research looked at nineteenth-century antiquarianism, which has traditionally been seen as the precursor to systematic and scientific methods of archaeological practice. However, during the nineteenth century the study of ‘antiquities’ included objects, monuments and manuscripts, with scholars focusing on the history of society, culture and civilisation from prehistoric to historic periods. Throughout my PhD I was constantly thinking about whether there is a difference between historical archaeologists and material culture historians. I do not think there is an answer, as every person has a different perspective and the ambiguity and interdisciplinarity in these fields prompts researchers to keep asking new and interesting questions of their sources. From my own work, I would define the history of archaeology as the study of the development of scholarship which focuses on material culture and the history of society, whether this is through excavation, material culture analysis, or the study of objects and culture through manuscript research, and that the history of archaeology also includes how objects were collected and displayed in private collections and museums. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? JH: I recently completed my thesis titled ‘Collecting the Nation: Scottish History, Patriotism and Antiquarianism after Scott (1832-91)’, which critically examined the interface between the expansion of the Scottish historical collection in the museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and the development of modern Scottish historiographical practices. My research analysed the relationships between collecting, representing, and writing about the Scottish past from 1832 to 1891, and considered the intersections between antiquarianism, Scottish history, material culture studies, archaeology, collecting practices, and museum development in the nineteenth century. Although my research focused on Scotland, I also compared museums across the British Isles, which I found really interesting for considering similarities and differences in methods of classification and display. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? JH: I originally did an MLitt in Museum and Gallery Studies at the University of St Andrews, and it was while I was doing my dissertation that I became interested in the history of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, their museum, and the history of archaeology and material culture research. My dissertation examined the motivations behind the acquisition of 100 ‘folk art’ objects from different parts of Scandinavia, currently held by National Museums Scotland. I then successfully applied for an AHRC-funded collaborative PhD at the University of Glasgow and National Museums Scotland as detailed above. It was during my PhD research that I really started to appreciate how the development of archaeological ideas and methods had a significant influence on the expansion and study of the Scottish historical collection in the museum. It was thought-provoking to see how perceptions on the value of material culture as a primary source also affected whether objects were used (or not) in nineteenth-century national histories of Scotland and how an increased interest in studying historical objects prompted the emergence of a separate body of material culture histories. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? JH: I am currently working on converting my thesis into separate articles, one of which has been accepted for publication and will be available November 2022. I am also working on an essay for an edited volume that looks at the ways in which objects connected to Mary Queen of Scots were displayed and interpreted in the nineteenth century. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? JH: Really getting to know the people behind the history of archaeology. The networks of influence and the social nature of antiquarian and archaeological societies was really important to how material culture studies developed. This was not only within Scotland, but through connections with other antiquaries and museums around the world. The first thing I did at the beginning of my PhD was read through 60 years of the Society’s minute books and it was like being immersed in a favourite soap opera. I think the human friendships, rivalries, arguments and fallibilities that underpinned the development of archaeological ideas and approaches is the most meaningful thing that I have come across as it gave the social context to ideological developments. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. JH: For anyone interested in the history of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland the edited collection A. Bell (ed) The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition is an essential go to. I cannot even count how many times I have come back to this text to check details and information. Rosemary Sweet’s Antiquaries: The Discovery of the Past in Eighteenth-Century Britain was a key text for me during my MLitt and when I started my PhD, and Sweet’s current research extends into nineteenth-century antiquarianism. Sweet’s work demonstrates how modern history, archaeology, and cultural history have their foundation in antiquarian ideas and approaches. Susan Pearce’s Museums, Objects and Collections has been a text that I have gone back to again and again and is great for those thinking about the relationship between objects, museums and interpretation. AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting?

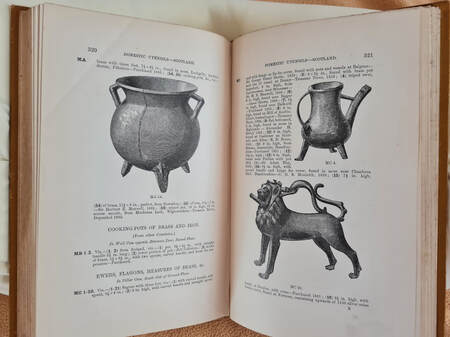

JH: The 1892 Catalogue of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland has been a text that has been essential to my research, and I keep revisiting. It contains so much detail on objects, donors, acquisition dates, and also uses the numbering still in use by NMS allowing me to identify objects and locate them in the museum. During lockdown, when the archives were closed, I managed to acquire my own copy of the catalogue that had previously been the property of Reverend Cecil Vincent Goddard, who collected on behalf of the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford. I still haven’t had to time to have a good look through his notes and additions. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? JH: Do not let yourself be impeded by notions of disciplinary boundaries. There are so many people who were important to the development of archaeology and material culture studies who have traditionally been left out of histories of the discipline as they have not been previously defined as archaeologists; their histories need to be told too. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? JH: Redefining who should be included in a history of archaeology and making sure the stories of those who have been excluded in the past are given greater attention. It is great to see the establishment of Beyond Notability as a project that will start addressing this issue for expanding scholarship on the history of women in archaeology. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? JH: My Twitter account is @Julieh80 Blog posts Women collectors, Lady Associates and the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland – History Journal https://mqs.glasgow.ac.uk/index.php/2020/08/18/the-multiple-meanings-of-the-queen-mary-harp/ https://blog.nms.ac.uk/author/jholder/ Debbie is Education and Outreach Officer at the London School of Economics Library. She and I discussed many things including racism in the history of archaeology, emotions in the history of archaeology, making connections to wider histories and contexts, and the importance of good metadata in archives. Listen to our conversation here. You can find Debbie's two posts on Hilda Petrie and suffrage, written for this website here. Debbie's work published open access:

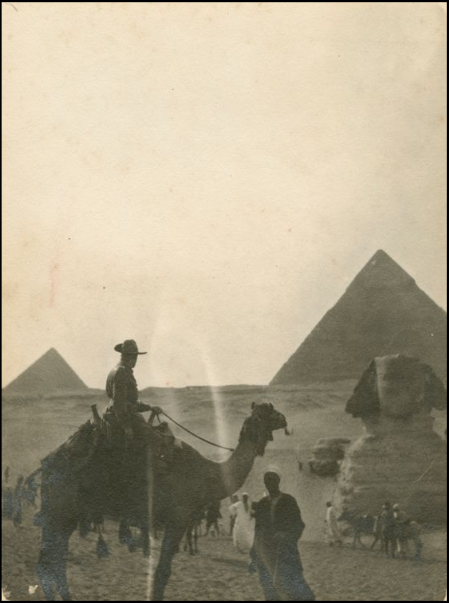

Challis, D., 2016. Skull Triangles: Flinders Petrie, Race Theory and Biometrics. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 26(1), p.Art. 5. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/bha-556 Open Access Challis, Debbie and Romain, Gemma (2015), A Fusion of Worlds. A / AS Level Learning Resource on the Equiano Centre Website, (Department of Geography UCL): https://www.ucl.ac.uk/equiano-centre/educational-resources/fusion-worlds/context/ancient-egypt-culture-and-barbarism [accessed 13 July 2020]. 2021: ‘Back to Back: Babies, Bodies, Boxes’ in Carruthers, W. 2021. Special Issue: Inequality and Race in the Histories of Archaeology. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, X(X): X, pp. 1–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bha-660 With Daniel Payne, ‘Giving Peace a Chance: Archives engagement at LSE Library’, Andrew H. W. Smith (ed.), Paper Trails. The social life of archives and collections, UCL Press: https://ucldigitalpress.co.uk/BOOC/3 2019, ‘Seeing Race in Biblical Egypt: Edwin Longsden Long’s Anno Domini (1883) and A. H. Sayce’s The Races of the Old Testament (1891)’, Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 28(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.2041-9015.1128 Debbie has put work she is now allowed to share and the introduction to her two books up here: https://lse.academia.edu/DebbieChallis Debbie's recent talk has been recorded and is available: https://events.bizzabo.com/aep/agenda/session/651358 (Registration needed) Other work referenced in the interview: Davies, Vanessa, 2019-20. W. E. B Du Bois, a new voice in Egyptology’s disciplinary history, ANKH. Can download from Academia: https://www.academia.edu/42746258/W._E._B._Du_Bois_a_new_voice_in_Egyptologys_disciplinary_history Gunning, Lucia Patrizio, 2021. Cultural Diplomacy in the acquisition of the head of the Satala Aphrodite for the British Museum. Journal of the History of Collections, fhab025, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhab025. Books with the most influence on Debbie when doing her PhD include Dominic Montserrat (2000) Akhenaten and Digging for Dreams, Ian Hodder and Scot Hudson (2003) Reading the Past. Current Approaches to Interpretation in Archaeology and Sven Lindqvist (1997) ‘Exterminate All the Brutes’. A book that influenced Debbie's writing The Archaeology of Race is Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins (ed.) The Object Reader (2009). The most recent and compelling books that I’ve read using archives, history, politics and objects are Phillippe Sande The Ratline (2020), Dan Hicks The Brutish Museum (2020) and Richard Overy Burning the books. Knowledge Under Attack (2020) James Donaldson is Manager and Curator of the RD Milns Antiquities Museum at the University of Queensland in Australia. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? JD: I see the history of archaeology as a reflective discipline, examining all aspects of archaeological and quasi-archaeological practice over the past several centuries (and perhaps even longer). It has to do with how archaeology used to be done, and how modern archaeology developed, but also with understanding the people who did archaeology and the social, historical and theoretical contexts in which they worked. I’m also interested in the history of formal and informal excavation at particular sites, what happened to the resulting finds, and what we can learn from re-examining those finds and the associated records. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? JD: I research the history of antiquities collecting and collections in Australia, with a particular focus on antiquities collected by Australians during the First World War. My aim is to understand why antiquities were appealing souvenirs for soldiers to bring back to Australia, what kinds of material they were acquiring, and where it is now. Australian service personnel took artefacts from every theatre where they served, from Mesopotamia to the UK, and there is evidence for a diverse range of collecting practices that had a big impact on the way public and private collections of ancient material developed in Australia. There is also the ethical aspect of collecting ancient cultural material during wartime: it is important to consider the relationship between antiquities as souvenirs and their status as items of foreign cultural heritage. A central part of my work is therefore to investigate how artefacts were collected during the war, how these practices relate to the broader context of colonial collecting and antiquarianism in the 19th and 20th centuries, and to promote transparency and dialogue about historical collecting activities and the ethics of antiquities collecting more broadly.

The current repository for this work is the First World War Antiquities Project. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? JD: My undergraduate degree was in Archaeology, but I then studied Classics for my Masters, while working as the manager of our Antiquities Museum at the University of Queensland. I became interested in the history of archaeology through provenance research, and research into the history of the UQ collection. This led to a further interest in how these archaeological collections developed around Australia, and some of the similarities in the way University and other collections were founded and used. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? I’m in the final stages of “Phase One” of the First World War Antiquities Project which has focused on collections from Queensland, including over 60 artefacts from 10 service personnel held by the Queensland Museum in Brisbane. An ongoing project is a biography of JH Iliffe, the first director of the Palestine Archaeological Museum in Jerusalem (now the Rockefeller Museum). Through a strange twist of fate, Iliffe’s archive of personal papers, three antiquities, and over 400 photographs came to be in Queensland and were donated to the University of Queensland’s Fryer Library in 2013. The Antiquities Museum received the artefacts and I curated an exhibition in 2019 on Iliffe’s archive. He spent almost 2 decades in Mandate Palestine in a position of considerable privilege as part of the British administration, and his archive and associated papers present a unique insight into the way Jerusalem was changing at this time, and the role of archaeology and the archaeological museum in these changes. A new project in my role with the RD Milns Antiquities Museum is to start documenting the modern marks on our antiquities collection, inspired by the Artefacts of Excavation project. It promises to be a surprising take on more traditional provenance research and the sources of antiquities held in Australian collections. AT: What, from your experience, is the most meaningful thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? JD: I really enjoyed the challenge of contributing to the first detailed listing of the JH Iliffe collection (based on the UQ Library’s initial accession listing) as part of our recent exhibition. It was a chance to get to grips with a sparsely documented collection, and start to sort out how it all fit together. The collection consists of over 400 photographs, alongside diaries, maps, notebooks and other ephemera, documenting a period of about 40-50 years of Iliffe’s life. It had some structure, but apart from a couple of brief obituaries and a few notes on the backs of photographs, there was very little to go on in terms of bringing order to the collection. It all came down to detective work, both within the collection and outside of it. It was exciting to see the narrative of Iliffe’s life emerge from texts, photographs and diaries, and to find important links to other archives around the world. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. JD: I think my favourite book on the topic is David Lowenthal’s The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge University Press, 1985). It discusses the way the past (including archaeological sites and research) are used, interpreted, preserved, changed and challenged. It is “good to think with” when trying to understand how archaeological finds, sites, evidence and the resulting thing we call “history” has been interpreted, and misused, by all areas of (western) society. Donald Malcolm Reid’s Whose Pharaohs? (University of California Press, 2002) and Contesting Antiquity in Egypt (American University in Cairo Press, 2015) are important syntheses of archaeology, museums, and modern identity in Egypt that bring together a lot of amazing archival material and ephemera that sits outside of “traditional” archaeology but is more in the realm of archaeological reception. I also enjoyed Susan Stewart’s work on collecting and the past in On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Duke University Press, 1993) and am looking forward to reading The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2020). AT: Is there a key object/ image/ text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? JD: The English poet Francis Brett Young (1884-1954) wrote a poem called “Song of the Dark Ages” in about 1916 while training on Salisbury Plain. He describes digging trenches in the chalk and finding “…calcined human bone: Poor relic of that Age of Stone, Whose ossuary was our spoil.” It goes on to reflect on the passage of time and the futility of the war, ending with the lines “And they will leave us both alone: Poor savages who wrought in stone – Poor savages who fought in France.” I keep coming back to this poem. There is something about this wretched reflection on the futility of the digging, the war, and the passing of time all concentrated on the discovery of ancient human remains that is so striking. Thousands of service personnel passed through Salisbury Plain for training during the war, saw the monuments, and speculated about them. Often this speculation was based on misunderstandings and out-of-date history (one soldier talks about Stonehenge being made by the Romans), but there is something very human about the intersection of archaeology/collecting/souveniring/remembering that I think speaks to why the history of archaeology is an important thing to study. AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? JD: I would encourage them not to be afraid to branch out from the established disciplines of archaeology or history or classics. There is so much work in interdisciplinary spaces, like the history of archaeology, but it is sometimes unclear how to get into these areas in standard university programs. Try to cultivate a wide interest in the past and different approaches to it. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? JD: History of archaeology is an emerging discipline in Australia and there is still a lot of foundational work to be done on understanding themes like the development of our old-world archaeological collections, and the history of Australian archaeological missions. There are great untapped archives of materials are universities and museums all around Australia, with links to other work happening around the world. A number of my colleagues are starting to undertake this research so it is an exciting time to be working in this area in Australia. There are also big questions to be asked about how and why “classical” and other forms of archaeology have been done in Australian and how they have contributed to museum collections and our collective understanding of the past. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? JD: I’m mainly active on my Twitter account where I share things related to First World War Antiquities and my work with UQ’s RD Milns Antiquities Museum. You can find me at @CairoJim. My work is also available on my ORDIC profile. Heba Abd El Gawad is an Egyptian Egyptologist and project researcher on the Egypt's Dispersed Heritage project (more information on the project below). She was co-curator of the Beyond Beauty exhibition at Two Temple Place in 2016 and the Listen to Her! exhibition at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology in 2018. We discussed the emotional impact of history of archaeology research, the role of social justice in the history of archaeology, and the ongoing legacies of colonialism. You can listen to our discussion here. The inspirational text Heba mentions in the discussion is by Egyptian geographer Gamal Habdan (1928-1993), a graduate of both Cairo University and the University of Reading. The work Heba refers to is entitled مجموعة شخصية مصر دراسة فى عبقرية المكان 4 أجزاء (The Character of Egypt). The quote from Amelia Edwards' 1877 book A Thousand Miles Up the Nile that Heba references in our discussion is: "I may say, indeed, that our life here was one long pursuit of the pleasures of the chase. The game, it is true, was prohibited; but we enjoyed it none the less because it was illegal. Perhaps we enjoyed it the more" (p.449-450) Heba has provided links to a number of additional project outputs:

Podcasts a) Who owns Egyptian heritage? podcast with Manchester Museum b) Our public panel on the legacies of Western colonialism on ancient Egypt and the link between ancient and modern Egypt chaired by BBC's Samira Ahmed at the National Museum in Scotland listen to this podcast c) You can listen to Heba discussing the Egypt's Dispersed Heritage project and her experience in curation in the latest episode of The Wonder House podcast, published Jan 2021. d) Heba has also been interviewed for the Manchester Museum podcast, published Feb 2021. Social Media Accounts The Egypt Dispersed Heritage project on Twitter and Facebook Comics Webinars: Project partnership with Egyptian comic artists producing Egyptian comic strips and graphic novels to confront colonial legacies of ancient Egyptian displays in Western museums, you can check out our interview with Digital Hammurabi and our comic artists' discussion panel for Everyday Orientalism. Human Remains webinar Your mummies, their ancestors webinar on the ethics of displaying and researching human remains in partnership with Egypt Exploration Society and Everyday Orientalism. Partnerships webpages a) For the Egypt Dispersed Heritage partnership with the Egypt Exploration Society to unpack its colonial legacy check this blog entry b) Project partnership with National Museum in Scotland check this English webpage and Arabic here. Media Coverage: Our project as Arab leading for Digital Comics during COVID 19 https://www.al-fanarmedia.org/2020/08/arabic-comics-reach-a-wider-audience-through-digital-projects/ a) Project in Egyptian Online News Network b) Project Comics in Egyptian Online News Network c) Project on Egyptian National TV Dr Lenia Kouneni is Associate Lecturer in Art History at the University of St Andrews. She has been researching and publishing on the history of archaeology and the history of collections in the late 18th/early 19th centuries, and the early 20th century, particularly in the latter case excavations at the Great Palace in Istanbul. This excavation was sponsored by David Russell, a Scottish philanthropist and industrialist, via the Walker Trust (for more information, see Lenia's 2018 blog post on artefacts from Jericho now held at the National Museum of Scotland). In addition to this work we discussed the allure of historic photographs and the importance of secretaries to our knowledge of archives and collections. You can listen to our discussion here. Miss Ilse Bell is the Secretary that Lenia introduces during our conversation. She has provided more details below: David Russell's personal secretary was Miss Ilse Bell. She became indispensable to him. She started working for him in 1917 until Russell's death in 1956. She translated articles for him, kept photographs organised and the correspondence too. She was an avid intrepid mountaineer and she spent all her holidays climbing mountains. Apart from the archaeological work of the Great Palace, she was also greatly involved in the Recording Scotland Project of the Pilgrim Trust during WWII. Lenia has a forthcoming chapter relevant to her discussion:

Kouneni, Lenia (forthcoming 2021) ‘ “By Scottish Munificence”: The Walker Trust Excavations of the Great Palace in Istanbul, 1935–1955.’ In Discovering Byzantium in Istanbul: Scholars, Institutions, and Challenges (1800–1955). Istanbul Research Institute. References/Further Reading: Barkan, Leonard, 1999. Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture. Yale University Press. Riggs, Christina, 2019. Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt, and the Archive. London: Bloomsbury. Stevenson, Alice, 2019. Scattered Finds: Archaeology, Egyptology and Museums. London: UCL Press. Meskell, Lynn (ed.), 1998. Archaeology Under Fire Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Routledge. Hicks, Dan, 2020. The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. Pluto Press. Thomas is Curator of the Cyprus Collection at the British Museum. Interview with Dr Amara Thornton, IoA History of Archaeology Network Coordinator. AT: How would you define history of archaeology? TK: In a basic way, it is – or at least should be – just a subsection of the histories of science/exploration/discovery, broadly defined, as well as I suppose of the disciplinary developments within archaeology itself. Tim Murray and others have noted how archaeology has tended to define its own history pretty much from the beginning of its institutional phase in the later 19th century, and has generally been written by archaeologists, so it has generally avoided the same scrutiny as the history of science which has a much broader disciplinary base. At the same time, it’s also a subsection of general imperial and colonial history, especially when carried out in areas that came under imperial and colonial control, and where diggers had explicit agenda – though saying that, the broader urge to explore and record can be found in among naturalists or ethnographers who often were interested in antiquities. More broadly still, it’s the history of ‘encounters’, including within countries where elite collectors and excavators (often local landowners and bigwigs) mapped out nations and controlled their histories through their recording of archaeological remains. One shouldn’t put as much emphasis on the social and political impact or aims/ideology of archaeology as is widespread nowadays, but I think you can represent the history of the subject as a search for origins and identities, but also of change and flux, regardless of where or how this actually happened. AT: What is your area of research in the history of archaeology? TK: Mainly 18th to 20th century Cyprus (and the Eastern Mediterranean in the same period more broadly), though working in a British Museum (BM) Mediterranean environment inevitably pans out into broader fields, such as museum procedures and admin – sounds dull, but is interesting (and certainly necessary) as we are very concerned about how we report and reflect our collecting history. I'm also fascinated by the role of the antiquities market in defining museum acquisitions and valorisation of artefacts. AT: How did you become interested in the history of archaeology? TK: Like lots of people interested in archaeology, I was fascinated by the history of discoveries, which is probably how a lot of us get into the subject. Ironically, that interest probably waned as I started to study archaeology at university. I remember the lecturer in my first year core archaeology class talking about antiquarians and old archaeological theories, but even if he didn’t like Processual archaeology, he tended to be relatively dismissive of earlier archaeologists. When I was doing my PhD, I saw the history of the subject as a sideshow, and like many just rolled my eyes at what I saw as the ridiculousness of early excavators, such as Luigi Palma di Cesnola. I certainly didn’t realise how important archives were for archaeological purposes, let alone broader historical questions. It was only when I started work at the BM, and began to engage with the subject from within the archive, that I got hooked – first because I realised that you couldn’t understand the collections archaeologically without knowing how they were found and handled, and then more historically in understanding the motivations of early archaeologists. Bit by bit, all the different bits of the subject coalesced into what I hope is a more joined-up interest in the subject. AT: Are you working on anything in particular related to the history of archaeology right now? TK: I’m finishing a big edition of correspondence relating to various phases of the history of Cypriot archaeology in the 19th century, from the late Ottoman consular activities to the fairly large-scale expeditions of the British Museum. Related to this, I’m also co-working on a paper on a Cypriot antiquarian and collector, Demetrios Pierides, and his relationship to the antiquity market – something that really interests me, as it’s very relevant to modern discussions of the trade. Finally, I’m also involved in a series of workshops on archaeology in the British colonial period in Cyprus with Lindy Crewe, Director of the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute in Nicosia and Anna Reeve, University of Leeds. It had to go virtual, but the benefit is now that you can all join in (www.caari.org/programs). AT: What, from your experience, is the most exciting thing you've come across in history of archaeology research and why? I think it’s fair to say that as in archaeology itself it’s often more a question of many small discoveries, and eureka moments when things start to connect in a way they didn’t at the beginning. Likewise with finding documents and photographs that you thought were missing, but were simply in a different file. Finding original photographs is always exciting, especially when they show local people – the elephant in the room of the history of archaeology. The edition of correspondence I mention above is joining up lots of individual stories and making sense of things which were very vague at the beginning. One very fun discovery was the Latin-based telegraphic code used by the British Museum’s supervisors in Cyprus to communicate with London. AT: Do you have any favourite books (academic or popular) related to the history of archaeology? Titles and authors would be great, and a few thoughts as to why. TK: I have to be loyal to the books that first inspired me. Henri-Paul Eydoux’s In search of lost worlds (whose original French title, A la recherche des mondes perdus is clearly a play on another far less interesting book!) and Michael Wood’s In search of the Trojan War – I bought this book after seeing the memorable TV show back in the day when a TV company would make a 6 part documentary on one subject! Of more recent titles, I really like Maya Jasanoff’s Edge of Empire, Zeynap Çelik’s About antiquities on Ottoman archaeology, while Jacqueline Yallop’s Magpies, squirrels and thieves is a great read on collecting more generally. Likewise, Karolyn Schindler’s biography of Dorothea Bate, Discovering Dorothea, is great – Bate was primarily a palaeontologist, but her contacts and networks all overlapped with archaeologists and their broader worlds. They all in a sense project a sense of the serendipity and subjectivity, of how much individuals shaped the disciplines (and often went against the social grain). They all have great narratives, which are essential to the subject itself, but especially in engaging broad audiences. I love reading old travel accounts too, even if you have to take a deep breath at the prejudices expressed. One great joy of working where I do is our stunning collection of early books of travel and exploration, especially archaeology, and it’s wonderful to look at them in their glorious original scale and smell. My department has two (!) sets of Richard Pococke’s Description of the East of 1751. It’s a marvel. Conversely, while I won’t name names, but there are also loads of rather mundane chronicles of archaeological discovery out there that leave a lot to be desired. And, lots of writing on the subject is frankly a bit dull, especially when aspiring to being hyper-intellectual. It kind of squeezes the joy out of the subject and leaves potential readers of critical history rather cold. AT: Is there a key object/image/text from an archive that inspires you or that you keep revisiting? TK: I really love the surviving field notebooks where excavators recorded their finds and began to grapple with what we would now call the ‘discipline of archaeology’. There is one by John Myres where he records the finds from tombs at Amathus in Cyprus a really meticulous way, but at the back are loads of scribbles and thoughts but also an attempt to ‘seriate’ the tombs in order to date them better. Myres has been called the ‘father of Cypriot archaeology’, and you can see his mind working, and the discipline coming into being in front of your eyes. I also love photographs, and one I have in mind shows a large marble capital from Salamis in Cyprus being dragged through the streets of Famagusta in 1891. It shows Royal Navy personnel and lots of local workers, but also the on-looking provide a kaleidoscope of the diverse late Ottoman/early British local community. Oh to have been there…

AT: Any advice for those interested in starting research on the history of archaeology? TK: Reads lots of older archaeological accounts and narratives of discoveries, rather than the many tedious commentaries on them that sometimes pass as historical analysis! You have to read the latter too, but try not to put Descartes before the horse… I think a solid grounding in the history of the region you are interested in is also essential. Things start making sense in an organic way, and you start to realise that archaeology was – in my view – not as important or ideological as is often said in narrow histories of the subject. This would also I think address some of the problems with the lack of knowledge of imperial history that is a big problem today (see next question). Also, develop an interest in biography, micro-history (and related empathetic approaches), and general narrative, but also in the materiality of archival documents – and I think working with archival documents is essential and exciting. Finding an archival niche is I think one of the things that open up the subject and connects with public audiences. AT: From your perspective, what are the key issues in the history of archaeology right now? TK: Well we are all post-colonial now, and there are a lot of discussions mediated through various post-colonial lenses that we have to address, especially the contextualised collection histories of museums and better understanding imperial history. How effective and convincing these discussions are remains moot because I think we tend to jump from very general post-colonial perspectives to very specific archaeological ones without a huge amount of nuance – hence my suggestion that we need to have a very solid grounding in general history. I think we certainly need to address under-representations of archaeological agency – especially gender (cherchez les femmes!) and local communities (from digger and foremen to local elites who collected and studied antiquities – and often collaborated with the acknowledged archaeologists). I think that is one of the key post-colonial insights we can advance with very little effort, just as social historians transformed how we saw history ‘at home’ in past decades. Global knowledge justice is certainly our remit too – the recent lockdown simply reinforced the problem of access to archives (and collections). I think if we could open up our archives in a digital way that would address some of the problems. Saying that, I think we also need to expand the public awareness of archaeological and museum histories far beyond present conceptions. AT: How can people learn more about your research (personal blog, twitter, etc)? TK: Despite what I said about the importance of digital, I don’t tweet or blog! You might find random visual musings on Instagram which I like to imagine as archaeological Wombling (nebulatrope). Maddy Pelling is an art historian specialising in the history of archaeology and collecting in the 18th and early 19th centuries. She is currently working on a postdoctoral project on the history of women antiquarians in the UK during this period. We discuss the evidence for women excavating, researching and publicising the material culture of the past, and the importance of local contexts, identity and colonialism in the history of archaeology. Listen to our conversation here. Follow Maddy on twitter @maddypelling.

Read Maddy's comments on the excavations at Warminster in the online edition of Vestuta Monumenta. Listen to Maddy's paper, "Digging Up the Past: Contested Territories and Women Archaeologists in 1780s Britain and Ireland" at the Open Digital Seminar in 18th Century Studies. Further Reading/References Lake, Crystal. 2020. Artifacts: How We Think and Write About Found Objects. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Raiders of the Lost Past with Janina Ramirez: The Sutton Hoo Hoard (BBC4) Dr Nicole Cochrane is a historian of archaeology specialising in the history of collecting in British museums in the 18th and 19th centuries. We discuss Nicole's route into research in the history of archaeology, her work on the Townley Gallery at the British Museum, and some inspirational objects and texts from her experiences. Listen to our conversation here. Find Nicole on Twitter @tinyhistorian. Further Reading

Bignamini, I. and Hornsby, C. 2010. Digging and Dealing in Eighteenth-Century Rome. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. Carruthers, W. (ed) 2014. Histories of Egyptology: Interdisciplinary Measures. London: Routledge. Procter, A. 2020. The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums and Why We Need To Talk About It. London: Cassell. Riggs, C. 2018. Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt and the Archive. London: Routledge. |

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed