History of Archaeology

|

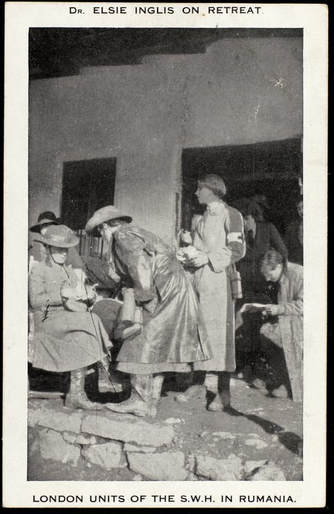

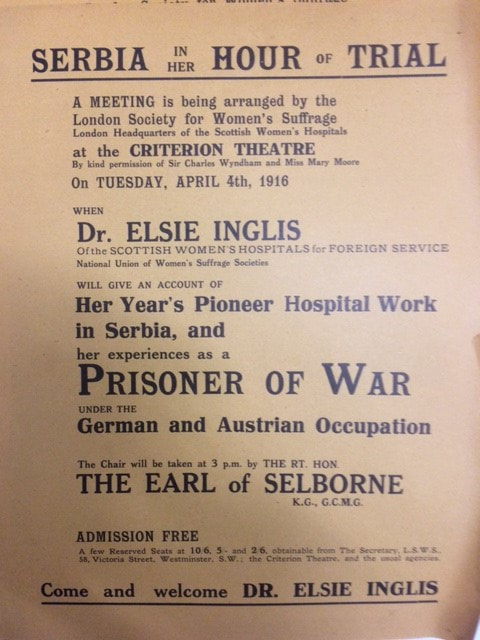

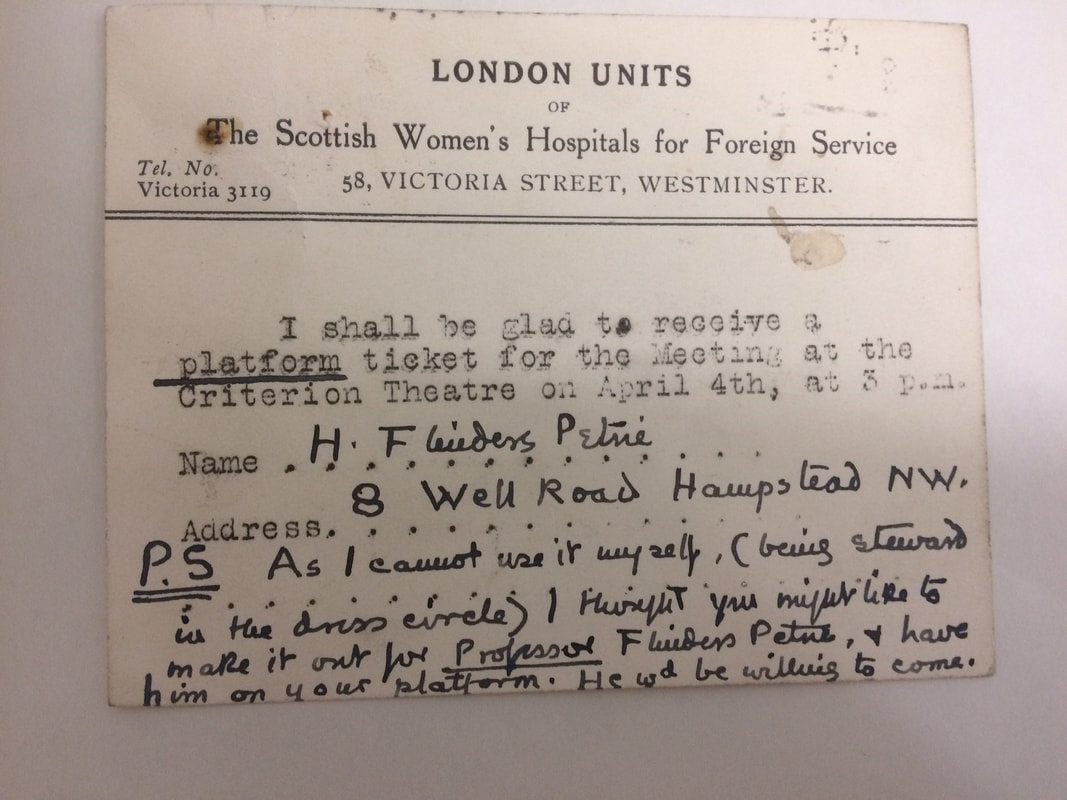

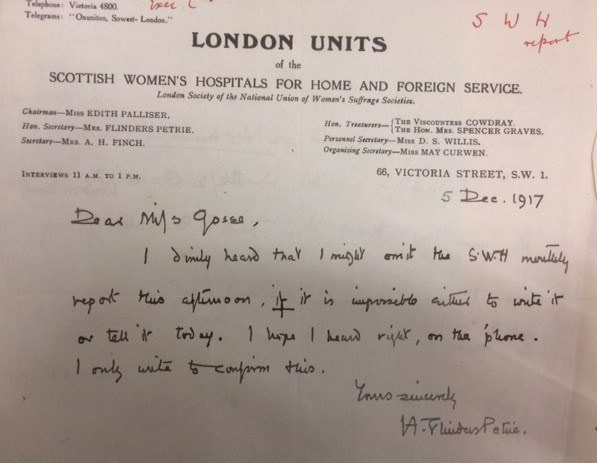

By Dr Debbie Challis (LSE Library) On the declaration of the First World War, suffrage work was ceased. Millicent Garrett Fawcett sent a message to the societies of the NUWSS: “Let us prove ourselves worth of citizenship, whether our claim be recognised or not”. Members of the NUWSS did not whole heartedly support war work – many were pacifists and internationalists. As the organisation was democratically run, there were fears of a split. In the event, organisations evolved from the suffrage societies as women applied the skills they had learnt or brought to suffrage campaigning to the war effort or, for more unpopular, movements for peace. Philippa Strachey, the secretary of the London Society of Women’s Suffrage (LSWS), was herself partially responsible for creating the Women’s Service Bureau in the first week of the war. This organisation came out of the LSWS and immediately began to find accommodation for Belgian refugees, organise War Relief Committees, hospital stores and dozens of other activities. Later it assisted in the recruitment of women for government and military positions, as well as munition workers. The experience of organising numerous suffrage rallies, committees, petitions and etc. were put to use by women. Flinders Petrie was a prominent public figure and involved in political issues and commentary as well as archaeology. Soon after the war began Petrie wrote a letter ‘How to be useful in war time’ to The Times on 21 August 1914 about factory conditions and the support of out of work garment makers. He suggested that the people put out of work in the clothes industry by the war were reemployed to make hospital clothes in readiness, such as was being done at University College Hospital, and that donations could be made to the Anti-Sweating League. Petrie provided "Miss Eckenstein"’s address at Greencroft Gardens for contributions. This was presumably Lina Eckenstein, an older friend of Hilda’s, who had been on excavations with her and was a campaigner for women’s suffrage. After the declaration of war there was an immediate slump in fashion, dress and clothes sales, with redundancies and considerable hardship amongst workers who, already existing on temporary contracts and low pay, had hand to mouth employment. Lina Eckenstein’s charity and Petrie’s publicising of it was one of a number of acts to assist redundant women from this industry. In addition, Hilda Petrie placed the subscriptions to the British School of Archaeology in Egypt into a war loan – people bought bonds or loans to help pay for the war effort. Hilda soon put all her fundraising efforts into the war effort, or rather a section of it. The surgeon Dr Elsie Inglis was a prominent Suffragist who was based in Edinburgh. She was a highly qualified and regarded doctor who had set up hospitals and trained other female doctors in Scotland. Inglis wanted to set up female run hospital units behind the main areas of fighting so teams of medics could treat casualties quickly. In September 1914 she approached both the NUWSS and the War Office to offer her services as a doctor and as an organiser. She was infamously ‘sent home’ by an official at the War Office and told ‘My good lady, go home and sit still’. Sitting still was not something Inglis did. She, fortunately, persuaded Millicent Fawcett and the NUWSS committee to assist her in setting up Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Home and Foreign Service, which was run from the former suffragist offices in Edinburgh. In October 1914 Inglis spoke on the scheme in a lecture ‘What women can do to help the war’ at Kingsway Hall in London and a London Units of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals was founded by early 1915. Edith Palliser, an elderly Irish suffragist, was the Chair, Hilda Flinders Petrie the Honorary Secretary and Viscountess Cowdray the treasurer. Inglis recruited and formed all women medical units. The Scottish Women’s Hospitals funded, assisted with recruitment, ordered and shipped supplies for these operations. The British War Office would have nothing to do with these units, but the Allies of France and Serbia gratefully accepted Inglis’ offer of help. Soon women’s hospitals were established in France in November 1914 and Serbia in 1915. In April 1915 the chief medical officer of the Serbian unit fell ill and Inglis went out to replace her. She established two further units in Serbia before the area she was working in was occupied by the Germans in the autumn. After becoming a prisoner of war, she was allowed to return home in February 1916. While in London and Edinburgh she organised awareness of the situation in Serbia, including a high profile lecture at the Criterion Theatre London the following day. Hilda Petrie was on the list of stewards for this lecture and display of support for the besieged Serbs – a handwritten list in the notes for this lecture records her being positioned in the dress circle. She was, however, also down to sit on the ‘platform’, i.e. on the stage as a high profile supporter and fundraiser. In a postcard note reply to the platform invitation, Hilda suggests that her husband Professor Flinders Petrie (she underlines professor!) takes her place. In the event, a seating diagram shows us that Flinders Petrie sat in stalls but as a platform ticket holder as there were so many on the platform already. Was Hilda in her role as war-time fundraiser and co-ordinator more important than her high profile husband? Inglis wanted to raise money for units in Mesopotamia but her plans were ‘sabotaged by the war office’ and later in the year she led a hospital unit to Southern Russia and ended up in Romania. The Unit left Liverpool for Odessa (there is a blow by blow account in E. S. McLaren’s Scottish Women’s Hospitals) and was specifically sponsored by the London Units. Hilda Petrie played a prominent role in reports and fundraising according to notes in the fundraising archives. Images of Elsie Inglis, presumably belonging to Hilda Petrie, were donated by her daughter Ann Petrie to the Imperial War Museum. The photograph of Inglis in the field was reproduced in newspapers, e.g. The Daily Record and Mail on 15 January 1917, and sold as a postcard, such as the copy reproduced here, presumably to make money for the war effort. There is an intriguing letter from Inglis to Hilda Petrie dated 8 May 1917 that is reproduced in Frances Balfour’s biography of Inglis, the first paragraph is quoted in full: Dear Mrs. Petrie,—How perfectly splendid about the Egyptologists. Miss Henderson brought me your message, saying how splendidly they are subscribing. That is of course all due to you, you wonderful woman. It was such a tantalising thing to hear that you had actually thought of coming out as an Administrator, and that you found you could not. I cannot tell you how splendid it would have been if you could have come.... I want “a woman of the world” ... and I want an adaptable person, who will talk to the innumerable officers who swarm about this place, and ride with the girls, and manage the officials! It reveals Hilda had evidently brought the subscriptions of ‘the Egyptologists’ to the London Units and had even considered making the journey to southern Russia herself. There is potentially more evidence of Hilda’s involvement in Inglis’ letters.  Postcard image of Dr Elsie Inglis and other women from the London units of Scottish Women's Hospitals in Romania, printed inscription front: 'DR ELSIE INGLIS ON RETREAT LONDON UNITS OF THE SWH IN RUMANIA', manuscript inscription reverse: 'Miss Stephenson Francis Holland School for Girls, Clarence Gate, NW Speaker for march on & other hand work. Monday March 12'. Scottish Women's Hospitals. The Women’s Collection at LSE Library. Inglis was gravely ill with stomach cancer in 1917 but, against the backdrop of the Russian revolution in 1917 and withdrawal of Russia from the war, she refused to leave battlefield until the Serbian units had safely left. Towards the end she directed others in carrying out surgical procedures as she was too weak to stand to do them herself. She finally reached Newcastle with other members of her unit, where she died on 26 November 1917. Hilda attended her funeral service on 30 November and the memorial service a week later at Westminster Abbey. According to the records of the London Units, Hilda continued with fundraising and co-ordinating work through the summer of 1918. She was presented to King George V and Queen Mary on 19 February 1918 with other members of her committee. I have only peered into some of the files of the London Units that we have at LSE Library. There is potentially more research that could be done around Hilda Petrie’s war work. I would argue that not only has her archaeological work and administration been overshadowed by her husband until relatively recently but also her work in World War One had an importance that we underestimate today. Lady Petrie’s obituary in The Times on 4 December 1956 was written by Margaret Murray, in which she mentions her ‘charm of words’ and how she ‘unaided raised the money’ for the excavations, and (crucially) by Lady Isabel Hutton. Hutton was a doctor who had served in the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and commanded the unit accompanying the Serbian army in its advance in 1918. Hutton wrote an accompanying letter in The Times on Hilda's death that Hilda supported her during the war and then after fundraised for the founding of the Serbian Medical Women’s Scholarship Fund and mentioned that a hospital Hilda worked hard to raise money for is still in use: It is rewarding to reflect that the establishments which Lady Petrie did so much to bring about in Yugoslavia not only continue to exist but go on developing and seem likely to do so for many years to come. Hilda’s legacy in southeastern Europe is yet to be understood. . . N.B. This note from Hilda, checking that what she heard on the phone was correct, reveals how members of the committee of the London Unit communicated. It indicates that these well to do women used their phones to do much of the day to day organisation, which may account for a relative lack of written correspondence. It is something to consider when looking for archives of organisations (especially those run by women?) from the 1910s onward. References / Further Reading:

Balfour, F. 1920. Dr. Elsie Inglis. London: Hodder & Stoughton. Lawrence, M. 1971. Shadow of Swords. A Biography of Elsie Inglis, London: Michael Joseph. Leneman, L. Inglis, Elsie Maud (1864-1917), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, published 23 September 2004, Https://doi.org/10.1093/ref;odnb/34101. Strachey, R. 1927. Women’s Suffrage and Women’s Service: The History of the London and National Society for Women’s Service, Westminster. Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed